Disordered Eating Patterns and Body Image Perception in Athletes and Non-Athletes Students

* Huma Hassan

Omama Tariq

Institute of Applied Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between body image perception and eating patterns in athletes and non athletes. The study also aimed to explore the gender difference of eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes. The cross-sectional research design and purposive sampling technique were used in this research. The sample size of the study was 160 (80 athletes and 80 non-athletes) students. Data were gathered from different institutes of Lahore that included University of the Punjab, Govt. College University, and University of the Lahore. Exclusion and inclusion criteria were selected. Research measures were used to assess the study variables i.e. eating patterns were measured by Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ; Strien, 2002) and body image perception was assessed by Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-16; Evans, 1993). Independent sample t-test and Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient were used to analyze the data. The findings of the study revealed that non-athletes students have more disordered eating patterns than athletes. On the other hand, no difference was observed in the body image perception in athletes and non-athletes. Results showed positive correlation between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes students. No gender differences were found between the disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes. The findings of the study have important implications for athlete and non-athlete adults and highlight the importance of counseling for students which in turn may help improve their eating patterns and perception regarding their body.

Keywords: : disordered eating patterns, body image perception, athletes, non-athletes

* Correspondance concerning this article should be addressed to Huma Hassan. Email: hassan.huma3@gmail.com

Body image is how we perceive our bodies. It greatly affects the mood of an individual. People with a good or satisfied body image feel happy and contented with their body while people with bad or unsatisfied body image are tend to feel disgruntled or hateful about how they look and how they perceive their bodies. Body image does not depend on what size or shape a person is; men and women who fit socially approved values of beauty feel confident about themselves, while other disapprove themselves if they don‟t fit themselves as socially approved and acceptable in society regarding how they look. Body image is the three-dimensional concept of one's self, recorded in the cortex by awareness of every changing body postures, and continuously changing with them (Tiffany & Meyer, 1995). Body image can be described as an individual´s body appearance and behaviors that he/she adopts to acquire better body image (Schawrz, Gairret, Aruguete, & Gold, 2005). Body experience is driven by everyday events (e.g., body exposure, social comparison, and social scrutiny, eating and exercising). These events activate schema driven processing of information about self- appraisal of one‟s appearance (Cash, 1996). Self- appraisal appears on existing attitudes of a person about body image and discrepancies between self-perceived and idealized physical traits; that result in implicit and explicit cognitions about one‟s body. These cognitions produce body image affect, which promotes adjustment strategies and behaviors in order to reduce unhealthy emotional consequences of a negative body appraisal. Such adjustment strategies can be relatively positive behaviors (e.g., seeking social assurance) that may reduce dysphoric experiences. On the other hand, such strategies and behaviors can be potentially harmful (e.g., unhealthy changes in exercise and diet) and likely to cause body image disturbance. Like any other person of general population, athletes and non- athletes (of both genders) are tend to develop harmful disordered eating patterns to acquire an ideal body image.

Disordered eating patterns refer to unhealthy or harmful eating patterns that are less frequent or less severe than diagnosed eating disorders (Muazzam & Khalid, 2008). The term disordered eating patterns emerged in medical and psychological literature in the late 1970s, coinciding with the introduction of diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa (Russell, 1979). Disordered eating was first used to describe dietary chaos and emotional instability experienced during recovery from anorexia nervosa (Palmer, 1979). The term was also used to describe young women, who occasionally indulge in dieting behavior, and lose weight more than 3 kg; as a result they may also experience episodes of binge eating, picking behavior, wish to be thinner, abuse laxatives or diuretics in order to achieve a preferred, „socially approved‟ slim figure (Abraham et al., 1983). Perez and Joiner (2003) defined disordered eating as bingeing, highly restrictive dieting, emotional eating or purging. Disordered eating patterns are not necessarily eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia. But they may be diagnosed as eating disorders not otherwise specified, sometimes referred to as EDNOS. This diagnosis is based upon the fact that a person has some of the characteristics of an eating disorder, but do not meet the full criteria of any eating disorder. For example, a girl who fulfill all criteria of anorexia but remains within a normal weight range or continues to menstruate may be diagnosed with an EDNOS (Natenshon, 1999). Strien (2002) proposed three theories of disordered eating patterns: Psychometric, external, and restraint. (i) Psychometric theory focuses on eating in response to emotional states such as anger, fear or anxiety. A normal response to emotional arousal and stress is loss of appetite and subsequent weight loss. However, for some individuals, emotional arousal and stress lead to an excessive intake of food. (ii) Externality theory highlights that the eating behavior or pattern of overweight individuals is comparatively unresponsive to internal physiological signs such as gastric motility. This theory focuses on the external environment as a determinant of eating behavior. (iii) Restraint theory attributes overeating to dieting. This paradox is based on the concept of natural weight; a range of body weight which is homeostatistically preserved by the individual attempt to lower body weight by conscious restriction of food intake initiates psychological defenses such as lowering the metabolic rate and arousal of persistent hunger. According to Strein (2002), these reasons may lead a person to disordered eating patterns. It has been proved by a number of researches that athletes and non-athletes are equally vulnerable to disordered eating patterns and negative body image perception. Body shape and unhealthy eating attitudes, which were once thought to be wholly confined to Western women, have also emerged in non- Western populations. The attitudes and behaviors of people towards body shape and weight in the West seem to be non- existent or uncommon in other cultures until such cultures begin to adopt the values of Western cultures. In traditional non-Western societies, a relatively fat body is considered as a sign of health and a symbol of prosperity (Mahmud & Crittenden, 2007). As compared to Westerns and other culture, less literature has been found on Muslim women with respect to body image. Islam explicitly de-emphasizes the color, shape and appearance of a person; instead it attributes importance to actions (Ahmed, Waller, & Verduyn, 1994).

Crago, Shisslak, and Estes (1996) highlighted that athletes suffer from more eating disorders than do non-athletes. Studies have shown that athletes report considerably less body satisfaction, more disordered eating behavior and a higher drive for thinness (Henriques, Calhoun, & Cann, 1996).

Bissell (2002) conducted a research which showed that in 80% of cases, athletes reported a greater desire than non- athletes to acquire and maintain ideal bodies while in other 20% of cases non- athletes has such desire. This indicates that athletes are more dissatisfied with their bodies than non- athletes. Non-athletes on the other hand appear to be more satisfied with their bodies, and if given the choice, would rather be overweight than underweight (Bissell, 2002).

Hallinan, Pierce, Evans, and Grenier (1991) conducted a research to examine the relationship between sex and perception of body image in athletes and non- athletes. By comparing existing body image and ideal body image; results showed significant distinction between women athletes and non- athletes. It was also found that non athlete women have unsatisfied body image as compared to athletes who are not associated with this perception.

Dick (1999) examined the relationship between gender, type of sport, body dissatisfaction, self-esteem and disordered eating behaviors in division I athletes. It was concluded that more than one third of National College Athletic Association (NCAA) division I women athletes showed symptoms that could put them at risk of suffering from eating disorders.

The research of Zucker et al. (1999) suggested that some athletes seem to associate being thin with success in their sports or activity. Because this performance related drive for thinness make some college athletes believe that with lower body fat, they will enhance performance in their sport.

Ahmad, Waller, and Verduyn (1994) conducted a research to examine the role of perceived parental control as a potential mediating factor between cultural issues and eating psychopathology. It was found that Asian girls living in the United Kingdom had more unhealthy eating attitudes than Caucasian girls. It has been suggested that this difference may be due to “cultural conflicts,” but that term needs to be operationalized by determining the underlying practical and psychological mechanisms. Asian girls had a greater level of bulimic tendencies than Caucasian girls, but a significant part of this difference was due to Asian girls' greater level of perceived maternal control. Perceived paternal control also masked an underlying tendency for the Caucasian girls to be more dissatisfied with their bodies than the Asian girls.

In another research Mahmud and Crittenden (2007) compared Australian and Pakistani women on body image attitudes. The sample consisted of Caucasian-Australian and Pakistani first year university students with the age range of 17 to 22 years. The Pakistani sample was subdivided into two groups: Urdu-medium and English-medium, representing the middle and upper social classes, respectively. The results revealed that, although all the groups identified a similar body shape as the „ideal‟ but Australian women expressed significantly higher levels of body dissatisfaction than did Pakistani women. Within the Pakistani sample, women from English-medium institutions expressed greater weight concern than did the Urdu-medium women.

Muazzam and Khalid (2008) also highlighted disordered eating behaviors in people of Asian cultures, especially Pakistan. They found that presence of eating disorders in Pakistan cannot be denied. The findings showed that disordered eating behaviors are more prevalent in Asian cultures than are eating disorders. The difference between disordered eating and occasional disruption of normal eating patterns is the urgency and the persistence behind the eating behavior. the analyses of research literature show an alarming rise in eating disorders in South Asian and Islamic countries.

Keeping in view the above findings on the basis of literature, it is summarized that people with negative body image are more vulnerable to disordered eating patterns. Through literature it was proved that athletes have more disordered eating patterns as they have more negative body image perception. And, at the same time, research proved that non- athletes have more disordered eating patterns.

Objective of the study

- To determine the difference of disordered eating patterns and body image perception between athletes and non- athletes.

- To explore the relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception.

- To determine the gender difference of disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes.

Hypothesis of the study

- There is likely to be a significant difference between the eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes.

- There is likely to be a significant relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception.

- There is likely to be a significant relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes.

- There is likely to be a significant relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in non- athletes.

- There is likely to be a significant relationship in five facets of disordered eating patterns {emotional eating, emotional eating (diffuse emotion), emotional eating (clearly labeled emotions), external eating, restraint eating} and body image perception.

- There is likely to be a gender difference between the eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes

Method

Research Design

The present research investigated disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes. The cross- sectional research design was used for the current study.

Sample

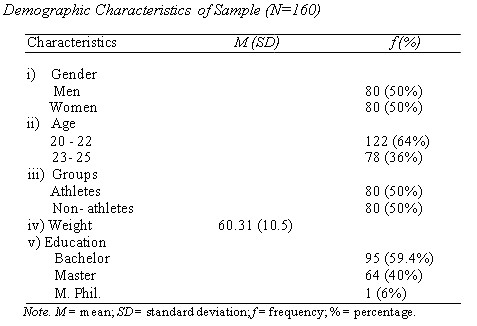

The purposive sampling technique was used in this study. The sample size of the study was 160 (80 athletes and 80 non-athletes) students with equal number of men and women. Data were gathered from the University of the Punjab, Govt. College University, and University of the Lahore. Exclusion and inclusion criteria were selected.

Assessment Measures

Demographic questionnaire.Demographic questionnaire of the current study included age, gender, education, name of the institute, height, current weight, meal timings, lowest weight, and episodes of unusual eating.

Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire ([DEBQ]; Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire ([DEBQ]; Strein, 2002).Eating patterns were measured with Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ; Strien, 2002). Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) assesses the structure of an individual‟s eating behavior corresponding to psychometric theory. It contains separate scales for emotional, external, and restrained eating behavior. Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) consists of 33 items (10 items for external eating, 10 items for restrained eating and 13 items for emotional eating). All items has a response rate on Likert scale of 1= never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, and 5=very often (Strien, 2002). Reliability of emotional eating was found .92 in men and .95 in women. On external eating, it was .80 in men and in women .81. On restraint eating, it was .93 in men and .95 in women (Strien, 2002).

Body Shape Questionnaire-16 ([BSQ-16]; Evans & Dolan, 1993).Body image was measured by Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-16, Evans & Dolan, 1993). The BSQ is a self-report measure of the body shape preoccupations. The BSQ was originally designed for use with women, but Melanie Bash (lead developer of the BSQ) has recently confirmed approved changes to three items allowing the BSQ to be used with men given the increasing prevalence of, and recognition of, eating disorders and body shape concerns, in men. All items had a response format of 1= never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often, 5=very often, and 6= always (Evans & Dolan, 1993). In an initial validation study concurrent validity was assessed by correlating the BSQ with other measures of eating disordered attitudes. For bulimic women a moderate (.35) but significant (p=.02) correlation between the BSQ and the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979) total scores, and a high correlation with body dissatisfaction was found. Reliability for BSQ-16 is .93 (Evans & Dolan, 1993).

Table 1

Procedure

Following logistic arrangements were made in order to conduct the current research i.e. official support letter by the supervisor, and permission for data collection was taken from the selected institutes. After getting permission from the authorities of different departments of selected institutes, the purpose of the research was briefly described to the participants. Consent and confidentiality regarding information and results were assured. After that, the demographic form and research questionnaire were administered by the participants of the study. Each participant took 10-15 minutes to complete questionnaires.

Ethical Considerations

In order to conduct this research, some ethical considerations were kept in mind. Both assessment tools for disordered eating patterns and body image perception were used after getting permission from the related authors through email. An authority letter from the Department of Applied Psychology University of the Punjab, Lahore was taken. Prior permission was sought from the departments of selected institutes for the purpose of data collection. Informed consent was presented to individuals to give them freedom to participate in the research.

Results

This research is a comparative study of disordered eating pattern and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes. The data strategy involved (i) Descriptive Analysis; (ii) Independent Sample Test was used to find gender differences and for finding the differences in disorder eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes; (iii) Pearson-Product Movement Correlation Analysis assessed the relationship between disordered eating pattern and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes students.

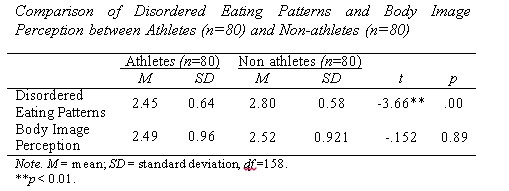

Table 2

It was hypothesized that there would be a significant difference between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes. Table 2 shows that non-athletes have more disordered eating patterns than athletes.

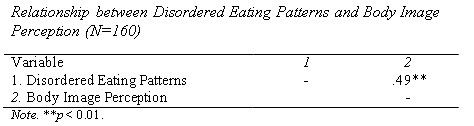

Table 3

It was hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception. Table 3 shows positive correlation between disordered eating patterns and body image perception.

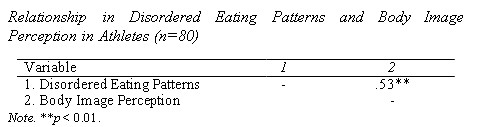

Table 4

Note. **p < 0.01.

It was hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship in body image perception and disordered eating patterns in athletes. Table 4 shows positive correlation between body image perception and disordered eating patterns in athletes.

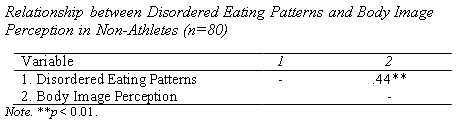

Table 5

Note. **p < 0.01.

It was hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between body image perception and disordered eating patterns in non-athletes. Table 5 shows positive correlation between body image perception and disordered eating patterns in athletes.

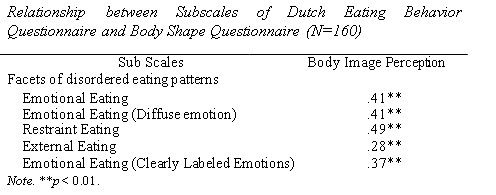

Table 6

Note. **p < 0.01.

It was hypothesized that disordered eating patterns would likely to have a relationship with the body image perception. Table 6 shows that all the subscales of disordered eating pattern have a positive correlation with the body image perception. Results indicate that the first three subscales (Emotional Eating, Emotional Eating (Diffuse emotion), and Restraint Eating) are more related to body image as compared to other two (External Eating and Emotional Eating (Clearly Labeled Emotions)), but none of the subscales are positively correlated to body image perception.

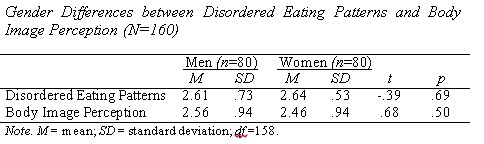

Table 7

It was hypothesized that there would be a gender differences in eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes (N=160). However, the result show no gender differences between study variables.

Discussion

Nowadays sports have significance in person‟s life than ever. Body image and perception create other issues that are compromising individual‟s way of living. Dietary behaviors lead an athlete to success; however unhealthy and harmful behaviors are also prevailing in an athlete‟s life i.e. disordered eating patterns. If a person does not have a positive body image, this can lead him or her to disordered eating behaviors. Perfectionism and strict discipline can definitely lead an athlete to achieve success, but taking it much seriously can harm physical and mental health of an athlete and lead towards disordered eating.

The research aimed to examine the relationship between body image perception and disordered eating patterns in athletes and non- athletes. The purpose of the present research was to ascertain if eating patterns are affected by how the person perceives his/her body.

It was hypothesized that there would be a significant difference between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes. The results showed that non-athletes have more disordered eating patterns than athletes. Sports require intense training and exercises due to which most of the athletes have an ideal body shape and ultimately have positive body image perception. Results show significance in non-athletes because of disordered eating patterns and unhealthy body image perception. Results of the present research are consistent with research conducted by Hallinan, Pierce, Evans, and Grenier (1991) and Wiggins and Moode (2000), which revealed that non-athletes have more disordered eating patterns than athletes.

The focus of the research was to find out the relationship between the disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes. In the present research, the correlational analysis indicated that there is a positive relationship between disordered eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non- athletes. Vohs, Heatherton, and Herrin (2001) examined the relationship between body image perceptions and disordered eating patterns, which also suggested that poor self-image, dieting behaviors, and eating disorder symptoms are correlated. Zucker et al. (1999) and Paul, Breeann, and Richard (1990) revealed that there is a significant relationship between the disturbed eating patterns and body image perception.

The correlation of subscales of eating patterns with the body image perception was measured. The results showed that all subscales of eating patterns have a correlation with the body image perception. Results also show that non- athletes with disordered eating patterns have inaccurate body image perceptions. Garner and Garfinkel (1979) conducted a research which showed positive significant correlation between Body Shape Questionnaire and Eating Attitude Test (EAT) with the reliability of 0.61.

Gender differences between disorder eating patterns and body image perception in athletes and non-athletes were also investigated in the current study. However, no gender differences were found. Smolak and Levine (1994) reported no gender differences in body dissatisfaction. Wilcox (1997) found no gender differences in body attitudes (as measured by the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire) in a sample of U.S. adults. There are few studies which report no gender differences of disordered eating patterns and body image perception. However, apparently, it is unclear why some studies report gender differences and others don‟t. Perhaps there are differences in regions, age, athletic status, family history, body mass index, etc. that would explain why some studies report gender differences in body dissatisfaction and some do not.

Implications

- The results should be explained to the non-athletes to let them know that in the pursuit of getting an ideal body, they can develop disordered eating patterns

- Seminars on building the awareness on the difference between healthy and unhealthy eating patterns should be arranged for young athletes and non-athletes in colleges and universities.

- The parents should also know the difference between healthy and unhealthy eating patterns so they can guide their children.

- Most of the adolescents develop the desire for a perfect body shape from media. So, with the help of the media, positive changes in the thinking of adolescents should be brought about.

Limitations

Following were some of the limitations of the present research:

- The permission from the concerned authorities took a lot of time. So it reduced the pace of data collection.

- The time span provided for the data collection was limited.

- As the data had to be collected from the student athletes too, the availability of the athletes was a big issue because most of the time they were unavailable due to visits to other cities for their matches.

- The results of the research cannot be generalized as the sample was selected from a few institutes.

Suggestions

The present research can be implemented in various fields and can be broadened and generalized if the following points are taken into consideration:

- Disordered eating patterns and body image perception should be studied separately in athletes and non-athletes and the factors responsible for them should be brought to the surface.

- There is a strong need to conduct extensive work on identification of other contributing psychosocial factors related to eating behavior such as self-esteem and life style. Socioeconomic status in relation to disordered eating should be investigated to ascertain its true picture in our society.

- Family functioning of disordered eating individuals must also be studied to draw some conclusion for further implications.

- Larger samples are needed to explain the accurate prevalence and incidence rate in Pakistan.

- Awareness about disordered eating patterns in Pakistan should be developed because according to the findings of literature review the number of reported cases to doctors, practitioners and mental health professionals of disordered eating patterns is equal to zero.

References

Abraham, S. F., Mira, M., Beumont, P. J., Sowerbutts, T. D., & Jones, D. (1983). Eating behaviours in young women. The Medical Journal of Australia, 2, 225-228.

Ahmed. S., Waller, G., & Verduyn, C. (1994). Eating attitudes in Asian girls: The role of perceived parental control. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 91-97.

Bissell, K. L. (2002). I want to be thin like you: Gender and race as predictors of cultural expectations for thinness and attractiveness in women. New Photographer, 57, 4-12.

Cash, T. F. (2002). Cognitive behavioral perspectives on body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice, 38-46. New York: Guilford Press.

Crago, M., Shisslak, C. M., & Estes, L. S. (1997). Eating disturbances in American minority groups: A review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19, 239-248.

Dick, R. (1999). Athletes and eating disorders: The national collegiate athletic association study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26,179-188.

Evans, C. & Dolan, B. (1993). Body shape questionnaire: Derivation of shortened "alternate forms". International Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(3), 315-321.

Hallinan, C. J., Pierce, E. F., Evans, J. E., DeGrenier, J. D., & Andres, F. F. (1991). Perceptions of current and ideal body shape of athletes and nonathletes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 72(1), 123-130.

Henriques, G. R., Calhoun, L. G., & Cann, A. (1996). Ethnic differences in women‟s body satisfaction: An experimental investigation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136, 689-697.

Mahmud, N. & Crittenden, N. (2007). A comparative study of body image of Australian and Pakistani young females. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 187–197.

Muazzam, A. & Khalid, R. (2008). Disordered eating behaviors: An overview of Asian Cultures. Journal of Pakistan Psychiatric Society, 5(2), 76.

Natenshon, A. H. (1999). When your child has an eating disorder.