Researchers Pawijit et al. (2017) discovered a connection between students' body dissatisfaction and anxiety, which was exacerbated by a worry of receiving a negative evaluation. Furthermore, Carper and colleagues (2010) found that pressures attributable to media influence increased the correlation between anxiety and body dissatisfaction. All males showed this, although homosexual men showed a stronger association than heterosexual men did.

These results imply that men who are unhappy with their bodies are more likely to report experiencing anxiety than men who are not; however, the evidence is mostly restricted to Body Dissatisfaction related to muscularity and thinness. The latter literature discussion provides a rational to study the relationship between Body Dissatisfaction and Appearance Anxiety which is the aim of the current study. A study was conducted to ascertain how idealized media representations affect young women's body shame and appearance anxiety, as well as whether or not these effects rely on the type of commercial and the participants' self-objectification. Body shame and appearance anxiety were measured both before and after the exposure. The findings demonstrated that idealized images in ads raised appearance anxiety after watching them. There was also a noteworthy correlation found between the idealized body and self-objectification. Regardless of the type of advertisement, participants' body shame increased after being exposed to idealized photos (Monro & Huon, 2005).

Men have given an account of amplified amount of dissatisfaction with their physical appearance over the past 30 years (Ogden & Mundray, 1996; Farquhar & Wasylkiw, 2007). Men who desired lesser body fat and increased muscle focused on the abdomen and the upper body, attempting to attain this ideal by extreme exercising and dieting (Ogden & Mundray, 1996; Baird & Grieve, 2006). The research results pointed out that the failure to meet the societal and cultural expectations of muscularity and masculinity funded to these ongoing issues.

To put it all together, Self-Objectification concerns in men have not been targeted in literature as extensively as that of women. Objectification theory also posits wide variety of literature mostly on women; however, recent research has now started to encompass male population in their study samples. The studies previously mentioned have suggested relationship that this study aims to find. The males in media are increasingly objectified and the lack of literature to acknowledge the associated symptoms (appearance anxiety) proposes the need to conduct this study. The latter mentioned studies also provide the groundwork of this study. The studies suggest that Internalization of media ideals, self-objectification and Body Dissatisfaction are further found to have a relationship with certain psychological concerns, i.e., appearance anxiety. Increasing objectification in men and their psychological concerns prompted this study.

It is vital to investigate the psychological effects of the latter factors because there is a dearth of research in Pakistan on subjects like Internalization of Media Ideals, Body Dissatisfaction, Self-Objectification, and Appearance Anxiety. According to recent studies, Asian countries have a high prevalence of body dissatisfaction (Tsai et al., 2003; Chng & Fassnacht, 2016; Izydorczyk et al., 2020). Males desired a strong body, whereas females selected a tiny, thin body size, according to Khor et al. (2009).

The present study will be fruitful in so many ways. Not only in clinical settings, but it ought to provide various benefits in the educational settings as well. The mental health professional or practitioners can develop an insight among the individuals and help them reflect on how media ideals have an impact on appearance anxiety and what could be done to prevent it. Moreover, the practitioners will be able to come up with certain interventions to deal with disturbing consequences on males of internalizing media ideals. In educational settings, this study could be used to educate the students in universities by conducting workshops and seminars by experienced psychologist and practitioners. This can develop awareness among the individuals who are not aware of the effects that Body Dissatisfaction and self-objectification could have on their psychological well-being along with the physical well-being.

Following theories help explain internalization of media ideals and how it heightens Self- Objectification and Body Dissatisfaction explaining the link to Appearance Anxiety:

Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997)

A person who starts to see themselves in the third person is said to be Self-Objectifying. According to the Objectification Theory, young girls and women internalize these ideals when they are repeatedly exposed to sexually objectifying experiences and when society as a whole supports the appropriateness of the practices mentioned above. This leads them to perceive their bodies as objects that others should examine, a concept known as Self-Objectification.

Cultivation Theory (Gerbner, 2002)

According to the Cultivation Theory, people are less likely to recognize the unrealistic nature of society's ideal body image the more frequently they are exposed to it. But if someone doesn't get this, they'll suffer from it and develop a bad self-image, which leads to body dissatisfaction.

Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954)

Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954) reflects the principle that people are compelled to evaluate or compare their own and others’ opinions and activities.

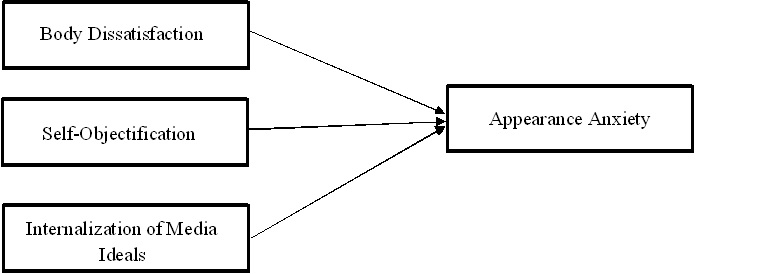

Note.The above-mentioned diagram is a proposed theoretical framework derived from the mentioned theories.

In the light of the above-mentioned figure, the current study aims to find out the impact Body Dissatisfaction, Self-Objectification and Internalization of Media Ideals has on Appearance Anxiety. And it was hypothesized that (1) There will be a relationship between Internalization Of Media Ideals and Appearance Anxiety in males. (2) There will be a relationship between Self-Objectification and Appearance Anxiety in males. (3) There will be a relationship between Body Dissatisfaction and Appearance Anxiety in males.

Method

The present study has a Quantitative Correlational Research Design. This design was used to see impact of three variables: Internalization of Media Ideals, Self-Objectification, and Body Dissatisfaction on Appearance Anxiety in males. The male participants were selected through purposive convenient sampling (non- probability sampling). The participants were approached on a availability bases i.e. any male falling within the age bracket was approached and briefed about the study and was asked to fill the questionnaire as per their agreement.

Assessment Measures

Appearance Anxiety Scale (AAS-Brief Version) (Dion et al. 1990)

The Appearance Anxiety Scale (AAS-Brief Version) has a total of 14 items and is used to measure anxiety as far as their bodies are concerned. AAS is a 5-point Likert Scale that ranges from 1-Never to 5-Almost Always. It has a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.86.

Internalization Sub-Scale for Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-III) (Thompson et al., 2004)

SATAQ-III is also used to assess a specific kind of self-objectification that is internalization of thin-ideal stereotype. SATAQ-III is a 5-point Likert scale, and has a total of 9 items. Also, this scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 as per the previous studies. This scale was adapted by focusing on the study by Zulqarnain, W. (2017), since there is a cultural difference in the media usage in Pakistan.

Male Body Dissatisfaction Scale (MBDS) (Ochner, 2009)

The final version Male Body Dissatisfaction Scale (MBDS) is a 5-point likert scale which has a total of 25 items. It measures how an individual feels about their body at the current state. Also, the participants are supposed to rate items on a scale from 1 to 10, indicating which item has more importance for them. Cronbach’s Alpha for this scale is 0.93.

Self-Objectification Scale (SOS) (Dahl, 2014)

SOS revised pool has a total of 28 items, which assesses how much value individuals associate with their looks and appearances. It is a 5-point Likert Scale and has a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.75.

Procedure

Male students (age group 18-25) from various public and private universities of Karachi were approached. A consent form was provided initially, and a demographic information form was attached to it, to obtain basic information about the participants. Each participant was then asked to fill four questionnaires. Appearance Anxiety Scale was filled first, then Internalization Sub- Scale for Socio-cultural attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-I). After which Self-Objectification Scale (SOS) and Male Body Dissatisfaction Scale (MBDS) were provided. These questionnaires took 10 to 15 minutes to be filled on average, and confusing items were explained. Permission of all the scales was available.

Results

Table 1

Correlation Analysis between Internalization of Media Ideals, Self-Objectification and Body Dissatisfaction and Appearance Anxiety.

|

AA |

IM |

SO |

BD |

|

|

AA |

1 |

.20** |

.15** |

.20** |

|

IM |

1 |

.35** |

.20** |

|

|

SO |

1 |

.11* |

||

|

BD |

1 |

Note.AA= Appearance Anxiety, IM=Internalization of Media Ideals, SO=Self-Objectification, BD=Body Dissatisfaction (**p<0.01)(*p<0.05).

The above-mentioned tables represents that there is a weak positive relationship between Internalization of Media Ideals and Appearance Anxiety in males. Furthermore, there is a weak positive relationship between Self-Objectification and Appearance Anxiety in males. There is also a weak positive relationship between Body Dissatisfaction and Appearance Anxiety in males.

Table 2

Simple linear Regression analysis showing the impact of Internalization of Media Ideals on Appearance Anxiety in males.

|

Appearance Anxiety |

|||||

|

Β |

B |

p |

R2 |

∆R 2 |

|

|

Internalization of Media Ideals |

.20 |

.23 |

.00 |

.041 |

.038 |

Note.β = Standardized Beta, R 2 = R – squared, ∆R 2 = Adjusted R – squared.

The result from the above-mentioned table indicates that Appearance Anxiety in males is only 3.8% predictable by Internalization of Media Ideals, which is a very weak relationship.

Table 3

Simple linear Regression analysis showing the impact of Self-Objectification on Appearance Anxiety in males.

|

Appearance Anxiety |

|||||

|

Β |

B |

p |

R2 |

∆R 2 |

|

|

Self-Objectification |

.145 |

.076 |

.00 |

.021 |

.018 |

Note.β = Standardized Beta, R 2 = R – squared, ∆R 2 = Adjusted R – squared.

The results from the above-mentioned table indicates that Appearance Anxiety in males is only 1.8% predictable by Self- Objectification, which is a very weak relationship.

Table 4

Simple linear Regression analysis showing the impact of Body Dissatisfaction on Appearance Anxiety in males.

|

Appearance Anxiety |

|||||

|

Β |

B |

p |

R2 |

∆R 2 |

|

|

Body Dissatisfaction |

.196 |

.114 |

.00 |

.039 |

.036 |

Note.β = Standardized Beta, R 2 = R – squared, ∆R 2 = Adjusted R – squared.

The results from the above – mentioned table indicate that Appearance Anxiety in males is only 3.6% predictable by Body Dissatisfaction, which is a very weak relationship.

Table 5

Simple linear Regression analysis showing the impact of Internalization of Media Ideals in Self- Objectification in males.

|

Self-Objectification |

|||||

|

Β |

B |

p |

R2 |

∆R 2 |

|

|

Internalization of Media Ideals |

.354 |

.749 |

.00 |

.125 |

.122 |

Note.β = Standardized Beta, R 2 = R – squared, ∆R 2 = Adjusted R – squared.

The result from the above-mentioned table indicates that Self-Objectification in males is 12.2% predictable by Internalization of Media Ideals, which is a considerable relationship.

Discussion

The hypothesis that there will be a relationship between Internalization of Media Ideals on Appearance Anxiety in males was proved (r (334) = .20, p < 0.01). Internalization of Media Ideals (IM) had the highest correlation with Appearance Anxiety in males. The extent to which media portrayals of gendered beauty ideals contribute to disturbances linked to body image and appearance anxiety is still debatable, despite a wealth of experimental evidence showing the detrimental impacts of internalizing media ideals (Moradi & Huang, 2008). When a desired body is not attained, internalizing beauty standards or media ideals causes people to value the differences between their idealized bodies and their actual bodies, which leads to body dissatisfaction (Lawler & Nixon, 2011). Hypothesis 3 was also proved determining a relationship between Body Dissatisfaction and Appearance Anxiety (r(334)=.20, p < 0.01). Davis et al., (1993) put forth that male (ages 18–30) who were to a greater extent dissatisfied with their bodies experienced more anxiety related to their appearance. The results from the current study also support the latter mentioned study, since being dissatisfied with own’s body can result in greater anxiety related to appearance.

Hypothesis 2 was proved, providing a significant, however weak impact of Self-Objectification on Appearance Anxiety (r (334) = 0.15, p<0.01). According to the Objectification Theory, there are a number of detrimental psychological effects linked to appreciating one's body more for beauty than for performance.

However, Self-Objectification (SO) did show significant positive correlation (r(334)=0.35, p<0.01) with Internalization of Media Ideals (IM) that is the other predictor of this study. As

technology has developed, media has had a greater influence on people. As media exposure rises, the human mind is becoming more and more prone to objectification. Because of its widespread appeal, the media has the ability to promote a certain ideal body type, which can cause both men and women to objectify themselves. According to a longitudinal study by Dakanalis (2014), internalizing media standards predicted eventual self-objectification—the act of considering one's body and appearance from the perspective of an outsider—which in turn predicted unpleasant emotional experiences.

Religion is one more factor that might have contributed to these outcomes, in addition to the predictors of the current study. With a 97% Muslim majority, Pakistan is the second most populous Muslim nation in the world. Traditional Islamic principles are highly valued in Pakistani society, which is predominantly hierarchical in nature. Given that this study was conducted in a variety of private and public universities in Karachi, the sample was made up of intelligent, middle- class, Muslim male students who were growing up in the city's conservative but steadily developing society. Since Islam encourages Muslims to be grateful for how Allah has made them, many Muslims with strong beliefs are content with their looks and their submission to Allah’s will. This could be a strong reason of why the predictors of this study showed positive but weak correlation with appearance anxiety.

Limitations and Recommendations

Some of the limitations of the present study were that the questionnaires were very lengthy that was making the participants leave. Along with that, the questionnaire was very long and due to the slightly taboo topic of the study, a social desirability factor was observed.

For future recommendations, a pilot study can be conducted for the generalizability of the scales, and it is also recommended to do collect data from female population as well for a comparative analysis.

Conclusion

It can be concluded from the current study that Internalization of Media Ideal, Self – Objectification and Body Dissatisfaction has an impact on Appearance Anxiety in males, however the relationship is very weak, and the predictability is less than 4%.

References

Awais, M., Campus, S., Maqbool, P. K., Ali, F., & Bhatti, T. F. (2020). Social media’s contribution to self-sexualisation behaviours among male students: the mediating role of self-objectification and internalization of rewarded beauty. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 24 (3). http://dx.doi.org/10.13187/me.2021.2.338

Barnes, M., Abhyankar, P., Dimova, E., & Best, C. (2020). Associations between body dissatisfaction and self-reported anxiety and depression in otherwise healthy men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229268

Carper, T. L. M., Negy, C., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2010). Relations among media influence, body image, eating concerns, and sexual orientation in men: A preliminary investigation. Body Image, 7 (4), 301-309. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.07.002

Frith, H., & Gleeson, K. (2004). Clothing and Embodiment: Men Managing Body Image and Appearance. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5 (1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.40

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., Signorielli, N., & Shanahan, J. (2002). Growing up with television: Cultivation processes. In Media effects (pp. 53-78). Routledge.

Gerrard, O., Galli, N., Santurri, L., & Franklin, J. (2020). Examining body dissatisfaction in college men through the exploration of appearance anxiety and internalization of the mesomorphic ideal. Journal of American College Health , 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1704412

Grieve, F. G., Newton, C. C., Kelley, L., Miller, R. C., Jr., & Kerr, N. A. (2005). The Preferred Male Body Shapes of College Men and Women. Individual Differences Research, 3(3), 188–192.

Grogan, S. (2008). Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children (2nd ed.). Hove, UK: Routledge.

Izydorczyk, B., Truong Thi Khanh, H., Lizińczyk, S., Sitnik-Warchulska, K., Lipowska, M., & Gulbicka, A. (2020). Body dissatisfaction, restrictive, and bulimic behaviours among young women: A Polish–Japanese comparison. Nutrients, 12(3), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030666

Karazsia, B. T., van Dulmen, M. H., Wong, K., & Crowther, J. H. (2013). Thinking meta-theoretically about the role of internalization in the development of body dissatisfaction and body change behaviors. Body Image, 10(4), 433-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.005

Khor, G. L., Zalilah, M. S., Phan, Y. Y., Ang, M., Maznah, B., & Norimah, A. K. (2009). Perceptions of body image among Malaysian male and female adolescents. Singapore medical journal, 50(3), 303–311.

Lawler, M., & Nixon, E. (2011). Body dissatisfaction among adolescent boys and girls: the effects of body mass, peer appearance culture and internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of youth and adolescence, 40 (1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9500-2

Leit, R. A., Pope, H. G., Jr., & Gray, J. J. (2001). Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: The evolution of Playgirl centerfolds. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(1), 90–93. https://doi/10.1002/1098-108X(200101)29:1%3C90::AID-EAT15%3E3.0.CO;2-F

Michaels, M. S., Parent, M. C., & Moradi, B. (2013). Does exposure to muscularity-idealizing images have self-objectification consequences for heterosexual and sexual minority men? Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14 (2), 175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027259

Monro, F., & Huon, G. (2005). Media-portrayed idealized images, body shame, and appearance anxiety. The International Journalof Eating Disorders, 38(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20153

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32 , 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1471-6402.2008.00452.x

Nielsen. (2016). The Total Audience Report: Q1 2016. New York, NY: Nielsen.

Pawijit, Y., Likhitsuwan, W., Ludington, J., & Pisitsungkagarn, K. (2019). Looks can be deceiving; body image dissatisfaction relates to social anxiety through fear of negative evaluation. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine And Health, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0031

Schooler, D., & Ward, L. M. (2006). Average Joes: Men's relationships with media, real bodies, and sexuality. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 7 (1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.7.1.27

Szymanski, D. M., & Henning, M. (2001). Self-objectification in men: Evidence of a curvilinear relationship with body satisfaction. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 2 , 149-158.

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): development and validation. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10257

Tsai, G., Curbow, B., & Heinberg, L. (2003). Sociocultural and developmental influences on body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors of Asian women. The Journal of Nervousand Mental Disease, 191(5), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMD.0000066153.64331.10