Self-Objectification, Objectified Body Consciousness and Eating Attitudes in Adults

Isra Tahseen*, Aasma Yousaf

University of the Punjab, Lahore

The objective of the current research was to discover self-objectification, objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes in adults. Hypotheses were: (1) There is likely to be a relationship in self objectification, objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes (2) Self objectification is likely to predict objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes. Total 161 participants ranging between 18-30 years of age were selected through non probability purposive sampling from different gyms in Lahore. Pearson Product Moment Correlation showed that self-objectification is positively related to eating attitudes, body surveillance and body shame whereas negatively correlated with appearance control beliefs. Multiple regression showed self-objectification as strongest predictor of appearance control beliefs and body surveillance. The study concludes that self-objectification is connected to faulty beliefs about self and disturbed eating attitudes which imply that realistic body goals need to be promoted in our society.

Keywords: objectification; body shame; eating attitudes

There is an expanding pattern of idealizing slim women and muscular men's bodies (Krring & Johnson, 2021). Feminist researchers have examined that how the process of the development of women's physique and bodies within particular social and cultural connections, influences the manner in which their bodies will be viewed, assessed and valued (Tiggemann & Slater, 2015). Actual interpersonal and social experiences, and mass media places women and men's bodies and body parts contributing in the spotlight towards a feeling or sense of self a woman or man has. From this viewpoint, men and women start to place unreasonable emphasis on physical appearance (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997).

Self-objectification has been theorized as the separation of a person's body, body parts, or sexual functions from his or her as a person, demeaning them to the status of sheer instruments/objects, or treating them as if they were able to represent him or her (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). The objectification theory argues that the most extreme impact of daily introduction that sexual objectification has is that it may prompt a situation where women or men adopt or internalize the perspectives of observers who objectify their bodies and they may start seeing themselves as an outside observer and treat themselves as an object just as other people do (Davis, 2018). Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) speculate that the nearly inexorable exposure to sexualized representations of women's body parts and bodies in the media and social media can lead to excessive habitual monitoring of the body (Butkowski, Dixon, & Weeks, 2019). Objectified body consciousness is the propensity to view one's own self as an object that is to be looked at and also scrutinized and evaluated by others (Lindberg et al., 2006). It comprises of three components as proposed by McKinley and Hyde (1996) namely body surveillance, body shame and appearance control beliefs (Moradi & Varnes, 2017). Body surveillance is the view of one's own body as another person or as an outside observer (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). Body surveillance is a term that was used by McKinley and Hyde (1996) to refer to the behavior in which a man/woman watch their body, and continually evaluate themselves in terms of how their body is looking instead of how it is feeling. Studies that are based on objectification theory have revealed that the constant monitoring of appearance along with self-objectification leads to an increase in the feelings of shame about one's body (Fredrickson et al., 1998). Body shame is defined as feeling or experiencing shame when one's body is not conforming to cultural standards (Holland & Haslam, 2016). When one consistently views the self from the perspective of the other, it may give birth to feelings of body shame (Wang et al., 2019). The major factor contributing to the development of body shame is the unattainable cultural standards for body shape (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). However, body shame can also be caused by societal influences and an urge to appear attractive to others. Body shame had been revealed to be related to decrease in body esteem and increase in restrictive eating behaviours and disordered eating (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). Eating attitudes are the maladaptive or disordered eating habits/attitudes adopted by people (Garner et al., 1982). There is a hairline difference between disordered eating/ eating attitudes and eating disorders. In disordered eating, caloric restriction, rigorous and excessive exercise, binging, purging, use of diuretics and laxatives etc may be present but the full criteria and severity of eating disorders is not present (Biber et al., 2006). Statistics for eating disorders in Pakistan are not available as this area has not been given much attention by Pakistani researchers especially concerning the prevalence of eating disorders. Nisa and Sohail (2002) identified that 59% of normal weight whereas 21% of underweight women considered themselves as overweight. According to the World Health Organization, 26% of women and 19% of men in Pakistan are either overweight or obese, with women being more prone towards obesity. Childhood obesity has also increased by 10% in Pakistan (The News, 2013). Women in the urban population have a higher tendency to be obese, than their rural counterparts (Tanzil & Jamali, 2016).

Williams and Tieggmann (2012) studied 146 Australian women undergraduate students ranging in age from 18-30 years and the results indicate that body shame was positively correlated with both self-objectification and body surveillance. Disordered eating was positively related to body shame, body surveillance and self-objectification.

Wagner (2011) studied 18 years and older women studying in university of Northwest Ohio and concludes that overweight women and women with normal weight, both experience objectifying experiences which lead to self-objectification, depression and eating problems, but overweight women exhibit more experiences of weight based objectification and more symptoms of disordered eating.

Kessler (2010) examined college women who went to gym for 5 days a week and found out that body surveillance was positively correlated with body shame. Body shame was positively correlated with eating attitudes.

A research study by Vandenbosch and Eggermont (2013) examines the relationship between one's exposure to sexualization on prime time television programs, pornographic websites, music on television and magazines for men with the internalization of appearance ideals, body surveillance and self-objectification among adolescent boys of different schools of Belgium. They conclude that significant correlations exist between internalization, body surveillance and self-objectification. It was also found that internalization of appearance ideals increased when boys spent more time viewing sexualizing television or pornographic sites. More consumption of pornographic sites was correlated with higher levels of body surveillance and an increase in self-objectification.

Colagero and Pina (2011) conducted a series of research studies, comprising two studies. In the first study, they used the survey method to explore the relationship between body guilt and objectification theory variables body shame, body surveillance and eating restraint. They took 225 women of southeastern British university as participants. The results indicates that high levels of body guilt was related to greater self-surveillance, increased experience of sexual objectification, increased body shame, as well as more eating restraint. In the second study, 85 women ranging from 18 to 34 years of age were recruited from southeastern British University. Results revealed that state self-objectification had positive correlation with body guilt, body surveillance, eating restraint and body shame. Self- surveillance was also positively correlated with eating restraint, body shame and body guilt. Body guilt was positively related to body guilt, and both these variables were also correlated with eating restraint.

The present study is focused on the effects of increasing cultural standards for a thin and ideal body. It was observed that there is an increasing trend of following fashion and wearing costumes that might be due to the influence of media and magazines. The current study would help to identify such trends in Pakistan. In Pakistani society, fair complexion and thin body is idealized as is the case in a majority of cultures. Girls are under constant pressure to reduce their weight in order to find a good husband and boys are also in constant state of worry to match their body with heroes in order to impress girls or spouses (Khan, 2013). The present study is also aimed at assessing the prevalence of self-objectification and its proposed correlation with objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes. The findings of this study will give a clear picture of at risk population for the eating disorders. The discoveries of this study will also help mental health professionals to provide guidance, and support to adults facing these issues. It is hypothesized that there is likely to be a relationship amongst self objectification, objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes in adults, whereas self-objectification is likely to have a positive relationship with body surveillance, body shame and eating attitudes and have a negative relationship with appearance control beliefs. It is also hypothesized that self-objectification is likely to predict objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes in adults

Method

The current study was using correlational research design and non-probability purposive sampling strategy to select participants for the study. The sample size was 161 participants and participants consisting of married (n= 83) and unmarried (n= 78) adults of which (n=78) were men and (n=83) were women. The age of the participants was 18-30 (M= 24.44, SD= 3.12) in range. The participants were selected from different gyms/ slimming centers in Lahore city. Adults who had joined the gym and were exercising there for at least 1 month as well as those who visited gym at least 5 days a week were included in the study. Adults with any physical disability such as upper or lower limb loss or disability, visual impairment, irregular gym participants, widowed and divorced adults, and pregnant women were excluded from the study.

Assessment Measures

Self-Objectification Questionnaire

This instrument measures the extent to which a person treats themselves as objects. The measure comprised of total 10 items, asking participants to rank order ten body attributes in order of their importance from 0-9. Scores can range from -25 to +25, with positive scores indicating self-objectification (Noll & Fredrickson, 1998). As mentioned and guided by Barbara L. Fredrickson, there is no internal consistency (a) because the scale is based on rankings not ratings (Personal Communication, June 24, 2015).

Objectified Body Consciousness Scale

The scale was used to measure body shame, body surveillance and appearance control beliefs, collectively referred to as objectified body consciousness. This scale was developed and validated by McKinley and Hyde (1996) and it has three subscales and each scale has 8 items, thus the total number of items is 24. Body surveillance subscale has internal consistency (a= .79), the Body Shame scale has internal reliability (a= .84) and Appearance control beliefs subscale has an internal reliability of (a= .72), respectively.

Eating Attitudes Test-26

Eating Attitude Test 26 (EAT-26) (Garner et al., 1982)was used to measure disordered eating attitudes. The EAT-26 consists of three subscales including Dieting having 13 items, Bulimia and Food Preoccupation consisting of 6 items, and Oral control having 7 items. The scale has a of .94 (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979).

Demographic Information Sheet

Demographic information sheet was created by the researcher which measured different demographics of the participants such as age and gender. Moreover, to check the cultural patterns present, exposure to television and magazines were also inquired through questions in the demographic sheet.

Procedure

Letters of permission were acquired from the original authors of the questionnaires for using and translating assessment measures for the this study. Permission was taken from the concerned authorities of selected gyms and nutrition clinics in writing of the pilot study. The pilot study was conducted in selected gyms and nutrition clinics after getting the permissions. A total of 20 men and women were approached for the pilot study. For the purpose of diverse sampling, gyms open in the streets/towns were also approached, at first to include adults belonging to low socioeconomic status but with time, the authorities of these gyms did not cooperate and the researcher felt unsafe in the environment so these gyms were excluded from the study due to security issues faced by the researcher during the pilot study. After the completion of the pilot study, required changes were made in the questionnaires which included the addition of some questions in the demographic information sheet. After the pilot study, it was identified that the majority of the participants were more comfortable with English version questionnaire so the main study was started in the selected gyms/nutrition clinics with original measures. Participants were provided the information about the objectives of the research using participant information sheet and consent was taken in written form. Then, the measuring instruments were administered individually to the participants in a set sequence with the demographic sheet, self objectification questionnaire, objectified body consciousness scale and eating attitudes test 26, respectively. A total of 190 participants were approached, out of which 20 participants refused to respond due to shortage of time. 9 of the participants were observed to have lacked of attention towards the administration, that is why these specific questionnaires were discarded due to the careless attitude of the respondents and many missing items. Afterwards, the results were calculated and interpreted by the researcher, keeping in mind ethical guidelines of privacy, confidentiality and informed consent.

Results

Pearson Product Moment Correlation analysis was carried out in order to establish the relationship between demographic variables like age, gender, television watching, magazine reading, and psychological variables in the study such as self objectification, objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes in adults. For the purpose of correlational analysis, categorical variable i.e gender was re-coded in the light of available literature and observed trend during the study. The most significant option according to the literature was termed as the baseline group, so women were coded as 1 and men as 0. The results of the correlation analysis are showed in table 1.

Table 1

Correlation Analysis of Demographic Characteristics, Self Objectification, Body Surveillance, Body Shame, Appearance Control Beliefs and Eating Attitudes in Adults

|

Measure |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

M |

SD |

|

1.Age |

- |

-.01 |

-.13 |

-.01 |

-.12 |

-.12 |

-.11 |

.10 |

-.06 |

24.4 |

3.12 |

|

2.Gender |

- |

.10 |

-.11 |

.24 ** |

.45 ** |

.17 * |

.03 |

.35 ** |

1.52 |

.50 |

|

|

3.TV watching |

- |

.25 ** |

.00 |

.07 |

.13 |

-.12 |

.15 * |

1.19 |

.40 |

||

|

4.Magazine |

- |

-.03 |

.02 |

.05 |

-.01 |

.04 |

1.34 |

.47 |

|||

|

5.SOQ |

- |

.31 ** |

.25 ** |

-.23 ** |

.27 ** |

1.66 |

10.37 |

||||

|

6.BS |

- |

.20 ** |

.13 |

.20 ** |

3.81 |

.97 |

|||||

|

7.BSh |

- |

-.19 * |

.36 ** |

4.25 |

1.05 |

||||||

|

8.ACB |

- |

-.11 |

3.74 |

.86 |

|||||||

|

9. EAT |

- |

23.09 |

11.08 |

Note.SOQ=Self Objectification, BS= Body Surveillance, BSh= Body Shame, ACB= Appearance Control Beliefs, EAT= Eating Attitudes.*p< .05, **p<.01

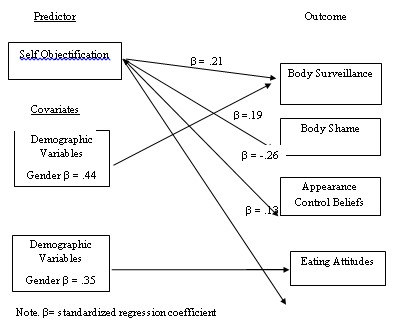

Multiple Hierarchal regression was also done in order to see the predictive effect of demographic variables and self objectification on body shame, body surveillance, appearance control beliefs and eating attitudes. Covariates (age, gender, tv watching and magazine reading) were also analyzed for prediction.

Table 2

Multiple Hierarchal Regression of Demographic Variables, Self Objectification, Body Surveillance, Body Shame, Appearance Control Beliefs and Eating Attitudes in Adults.

|

Predictors |

Body Surveillance |

Body Shame |

Appearance Control Beliefs |

Eating Attitudes |

|||||

|

?R2 |

? |

?R2 |

|

?R2 |

|

?R2 |

|

||

|

Model I Age Gender Tv Watching

|

.21*** |

-.15 .44*** -.04 -.07 |

.05 |

-.08 .14 -.06 .04 |

-.03 |

.13 .12 .01 .01 |

.20*** |

-.00 .35*** -.13 .03 |

|

Self Objectification |

.25** |

.21** |

.08* |

.19* |

.02** |

-.26** |

.21 |

.13 |

|

*p<.05, **p<.01,*** p<.005

Figure 1

Emerged Link between Self Objectification as Predictor of Body Surveillance, Body Shame, Appearance Control Beliefs and Eating Attitudes

Discussion

It was found that self objectification has positive relationship with body surveillance, body shame and eating attitudes in adults. Age has a negative relationship with self objectification meaning that increasing age lowers down self objectification. More exposure to television and magazines increases self objectification and its correlated variables. Self objectification is negatively related to appearance control beliefs. Self objectification came out to be a strong predictor of objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes in adults.

It was identified by descriptive statistics that women tend to read more magazines. This in turn increases women's self objectification, objectified body consciousness and eating attitudes. It can be interpreted that to have a desirable life, women tend to shape themselves according to prevalent trends. Hatton and Trautner (2011) argue that more objectification in media causes serious risks for mental health such as eating disorders and increases feeling of shame in viewers. The messages being provided in magazines by displaying white skin, a slim body is that if girls follow such a particular diet pattern or apply a specific whitening cream, they can acdvire a dream partner or a more successful married life (Ullah & Khan, 2014).

Television watching was found to be positively correlated to eating attitudes which is validated by a previous research done on Pakistani culture. Abideen et al. (2011) discuss the growing trend of presenting false images of slimming products and overly slim which models have impacted Pakistani youth in a negative way and it has changed the eating practices of youth leading towards various eating disorders. Moreover, faulty expectations are derived from mainstream media and dramas which appear on television which further add to maladaptive eating issues (Munir, 2021).

The results show that as age increases, self objectification decreases which is consistent with the work of Calogero and Pina (2011) as well as Tran (2021) who state that increasing age decreases the objectification and people do not incorporate third person's view of self. It is also consistent with the cultural trend that older women and men are supposed to be less concerned about their looks as well as dressing and are required to put on simple clothing to appear sophisticated.

The results show that men also experience self objectification. The reason for this trend is initiating Hollywood and Bollywood actors and trying to achieve the look of heroes, as reported by multiple gym coaches and also established previously (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2013).

Self objectification also predicted body surveillance. Moreover, gender came out to be the most significant predictor of all demographic variables. This trend has also been observed in previous studies as Calogero and Pina (2011) report the same results of self objectification predicting body surveillance. They also discuss the role of gender with women being more prone to experiencing both these problems. The reason for this gender variation is the high culture of today's media portraying women as mere instruments of attraction (Khan, 2013; Xiaojing, 2017). Body surveillance is also increased by fat talk which is very common in Pakistan (Abideen et al., 2011).

Self objectification also predicts appearance control beliefs, but in a negative direction which means that increased self objectification leads to lesser appearance control beliefs. As the person thinks more about his/her control over their bodies, they are less likely to experience self objectification (Boursier, Gioia & Griffiths, 2020). Moreover, it was also found that people who follow unattainable beauty standards such as white color and extra thin bodies, experience more self objectification leading towards the cognitions of inability to control body shape or weight (Ullah & Khan, 2014).

Self objectification strongly predicted eating attitudes as well, a result backed up by many previous researches. Fredrickson & Roberts (1997) discuss mental health risks of self objectification such as sexual dysfunction, depression and eating disorders with eating disorders being the most prevalent ones. Increased feeling of objectification leads to maladaptive eating attitudes as a compensatory behavior to reduce the difference between one's own body and cultural standards (Garner et al. 1982), as is observed in Pakistani society as well (Munir, 2021).

Conclusion

Self objectification is an ongoing issue and many adults are suffering its consequences as well. As a number of adults are vulnerable to developing an eating disorder. The present situation is mainly caused by overly objectifying media and subliminal messages provided by parents, teachers, peers and society as a whole. The cultural standards need to be redefined and people have to be educated regarding these issues for a better understanding of their problems.

References

Abideen, Z., Latif, A., Khan, S., & Farooq, W. (2010). Impact of Media on Development of Eating Disorders in Young Females of Pakistan. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 3(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v3n1p122

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association(7th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Biber, H. S., Leavy, P., Quinn, C. E., & Zoino, J. (2006). The mass marketing of disordered eating and eating disorders: The social psychology of women, thinness and culture. Women's Studies International Forum,29(2), 208-224.Pergamon.

Boursier, V., Gioia, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Objectified body consciousness, body image control in photos, and problematic social networking: The role of appearance control beliefs. Frontiers in Psychology,11, 147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00147

Butkowski, C. P., Dixon, T. L., & Weeks, K. (2019). Body Surveillance on Instagram: Examining the Role of Selfie Feedback Investment in Young Adult Women’s Body Image Concerns. Sex Roles.Journal of Research, 81(5-6), 385–397.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0993-6

Calogero, R. M., & Pina, A. (2011). Body guilt: Preliminary evidence for a further subjective experience of self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35,428-440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311408564

Claudat, K. (2013). The role of body surveillance, body shame, and body self-consciousness during sexual activities in women's sexual experience. http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations

Davis, S. E. (2018). Objectification, Sexualization, and Misrepresentation: Social-Media and the College Experience, I(1-9). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118786727

Dollar, E. P. (2014). "Inspiration Porn" objectifies people with disabilities. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ellen-painter-dollar/inspiration-porn

Garner, D. M., & Garfinkel, P.E. (1979). The Eating Attitude Test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9, 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700030762

Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The Eating Attitude Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine,12, 871-878. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6961471