South Asian Females’ Exposure to Childhood Violence and Perceived Stigma regarding Mental Health

Nithyyaa Thavapalan & Neelofar Rehman*

Australian Catholic University, Australia

Exposure to violence during childhood can have a long term detrimental impact on psychological health and wellbeing of affected individuals. The current study investigated the moderating role of stigma in relation to early exposure to violence and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among South Asian females. For this purpose, convenient sampling strategy was used in which 128 South Asian females of ages18 to 30 (M=23, SD=3.63) completed an online survey. Multiple regression analysis was employed. The results highlighted that exposure to violence during childhood is associated to higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress experienced among South Asian females in adulthood. The findings indicated that stigma associated with exposure to violence in childhood moderated the relationship among early exposure to violence, anxiety and stress experienced as an adult. The discussion emphasize es the need for understanding the role of stigma, associated with exposure to violence during childhood, in the manifestation of mental health issues among South Asian females.

Keywords: stigma; depression; anxiety; stress

Exposure to violence during childhood continues to remain highly prevalent with significant mental wellbeing implications across human lifespan (Holt et al., 2008; Norman et al., 2012; Sanderson, 2006). Violence towards children counted as social, human rights and public health issue with possibly devastating and costly consequences (Hillis et al., 2016). It is condoned and even sanctioned in communities worldwide, causing significant and often devastating effects in the long run on the children psychological well-being (Humphreys & Thiara, 2003). By one estimate, cumulative number of children vulnerable to violence is 275 million worldwide (WHO, 2014). At the national level, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017), over 66 percent of mothers within the general population reported their child witnessing violence and over one-sixth of the women experienced some form of sexual and/or physical abuse prior the age of 15. DV is defined by the World Health Organization (2002) as actions in a relationship including physical, financial, emotional, psychological and sexual abuse. It also consists of controlling behaviors comprising of isolating from close family and acquaintances, tracking movements and depriving of fundamental needs. In Australia, the term violence and Family Violence are used interchangeably (Campo, 2015).

Miller-Graff et al. (2015) suggests, exposure to violence during childhood is generally linked to higher levels of psychopathology symptoms. For instance, Zarling et al. (2013) found that children exposed to violence are posit higher risk of anxiety, and depression. Research has proven that these mental health concerns, associated with exposure to violence during childhood, can continue well into adulthood (Miller-Graff et al., 2015; Norman et al., 2012; Pico-Alfonsko et al., 2006; Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2005; Sanderson, 2006; Sternberg et al., 2006; Springer et al., 2007). However, limited research is present to inspect the moderating effects of age and exposure to violence and duration of violence exposure, on long-term mental health outcomes (Sternberg et al., 2006), including post-traumatic stress, mood and anxiety disorders.

While there is a link amongst childhood exposure to violence and adult mental health outcomes, the degree of this impact varies (Sanderson, 2006). This can be due to a number of psychological processes that may underlie or moderate the enduring effects of childhood experience of violence (Quinn et al., 2014). There is a significant impact of how victims of violence are perceived, treated by their community, and how they subsequently perceive themselves (Koss, 2000). This can consequently lead to social exclusion, discrimination and significant mental health concerns (Link & Phelan, 2001; Miller & Kaiser, 2001). Exposure to violence is usually kept hidden and the source of traumatic stress is usually not spoken about due to a number of factors such as shame and stigma. In this context the role of stigma needs further research and exploration.

Stigma is as a mark of shame and perceived negative attribute attached with certain human, situation, feeling or quality (Byrne, 2000). Stigma as part of traumagenic dynamics changes the way affected children cognitively and emotionally relate to the world. Thus, stigma has a direct bearing on the way children develop their self, emotion regulation mechanisms and form their view of the world. More specifically, feelings of guilt and shame, which encompass stigma, defined in literature as ingrained after effects of abuse found in child and adult survivors (Murray, Crowe & Akers, 2016). Finkelhor et al. (2013) further explain that traumagenic dynamics provide a rationale for understanding the process through which thoughts and feelings about trauma would be internalised and impact lifespan development. Literature highlights those dynamics such as stigma and self-culpability act as a mediator between sexual abuse in childhood and adult adjustment (Hillis, 2016). Stigma and its association with intimate partner violence (IPV) has also been explored and findings suggest that stigma can affect a survivor’s ability to seek help and recover (Murray et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2015; Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). Furthermore, Tourangeau and Yan (2007) demonstrated that research on sensitive topics, including violence, points towards participants’ tendency to underreport abuse, due to stigma, even in anonymous surveys.

Although violence, especially among immigrant minorities has been the focus of various studies however subject remains scarcely studied in South Asian cultures, precisely in the Australian context (Menjivar & Salcido, 2002; Midlarsky et al., 2006; Nguyen., 2007). While violence is endemic in different cultures/communities, it continues to be masked from public awareness due to various sociocultural practices in South Asian communities (Midlarsky et al., 2006). Generally, ‘South Asian’ denotes to individuals residing in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India. Within Australia, South Asian communities comprise a diverse group, which differ in religion, origin, language, and migration. Despite these differences, South Asians share common cultural values and practices, which include a strong commitment to retaining their cultural identity, keeping an immaculate image of oneself in the community, denying the presence of social issues like violence, and mental issues (Finkelhore et al., 2013). A culture of silence prevails in these communities’ preventing women from playing any role in the family and reporting any occurrence of violence. This raises great concern for all the vulnerable members in a family, in particular for children, who may directly and/or indirectly affected by violence (Midlarsky et al., 2006). Therefore, it becomes even more important to explore the stigma in adulthood, in relation to childhood exposure to violence and its link to long term mental vigor outcomes, among the communities with tendency to reinforce denial of any such exposure (Finkelhor et al., 2013). Numerous studies in South Asian communities on violence have been conducted in order to examine the prevalence of violence and support seeking behaviors of South Asian females suffering violence (Mahapatra, 2012; Raj & Silverman, 2002). Research indicates a noteworthy association between violence and long-term mental health concerns among South Asian females (Barn & Sidhu, 2002). This study aims to contributing to current literature by examining the moderating part of stigma in adulthood in relation to exposure to violence during childhood and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress experienced among South Asian females. It was hypothesized that exposure to violence during childhood would be related with elevated levels of depression, anxiety and stress experienced among South Asian females in adulthood. It was further hypothesized that stigma associated with exposure to violence during childhood, would moderate the link among violence exposure during childhood and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress experienced among South Asian females.

Method

ParticipantsUsing a convenience sampling strategy, 128 female participants of South Asian descent entered this study. Participants were of age range18-30 (M=23, SD=3.63). A total of 67.2% of the participants were of Srilankan decent, 26.6% Indian decent, 3.9% Bangladesh decent, 1.6% Pakistani decent and .8% Nepalese decent. The sample consisted of 21.1% of the participants completing high school, 3.1% TAFE (Technical and Further Education) degree/course, 59.4% an undergraduate equal education and 14.8% a post graduates. A total of 51.6% of participants reported their relationship status as being single, 32.8% reported being in a relationship, 12.5% reported being married, 2.3% reported to be living with a partner, and 8% reported being divorced.

Measures DemographicsDemographic information included: age, relationship status, ethnicity, level of education, age at exposure to violence (0-12 years) and duration of exposure to violence.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ-SF)

This scale consists of 23-items which measures experiences of abuse in childhood. Responses on each item range from 1 [never true] to 5 [very often true] (Bernstein et al., 2003). There are five sub scales of this measure comprising physical abuse (“Family member hit me with such intensity, causing bruises”), sexual abuse (tried to be touched in a sexual way by someone, or being forced to touch them”), and emotional abuse (Being called by names like “senseless,” “idle,” or “horrible”). All subscale covers 5 further items and 3 supplementary items for minimizing the degree of denying the abuse. Items are added for each sub scale with high scores representing more severity of particular type of abuse. Past research has found the scale to have an overall alpha coefficient of .91 (Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary & Forde, 2001). Cronbach’s alpha for the Childhood Trauma Scale came out .81.

Stigma Scale

This scale consists of 9-items, measuring the experiences about distress and other people's reactions to it (Gibson & Leitenberg, 2001). Item response tab ranges as 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). This measure includes items such as “How embarrassed you are about specific experience” and “How other people think about you if they get to know about what happened concerns you?”. Items are summed with high scores depicting severity of stigma. This scale has an overall internal consistency of .93 (Gibson & Leitenberg, 2001). Cronbach’s alpha for the stigma scale was .91.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS21)

This scale consists of 21 items measure of depression, anxiety and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Response scale of 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much) was used. Three sub areas including depression (“Life feel like meaningless to me”), anxiety (“I felt scared for no reason”), and stress (“It’s hard to relax”). Respective subscale contains 7 items and items are add up for each sub scale with large scores are indicator of greater severity of depression, anxiety or stress. DASS 21 has internal consistency and concurrent validity in the acceptable range bracket i.e., Cronbach's alpha of .87 (Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns & Swinson, 1998). In our study, Cronbach’s alpha for anxiety subscale was .96.

Procedure

Following the ethics approval by ACU Human Research Ethics Committee, an online survey was advertised through social media. Participants may withdraw from the research at all points. Participants completed the questionnaire through a protected survey website, Qualtrics. Responses collected were kept anonymous. By continuing past the first page of the survey, participants acknowledged informed consent and that they were over the age of 18. Those participants who indicated “yes” to exposure to violence were directed to complete the CTQ-SF, Stigma Questionnaire and the DASS-21, whilst those participants who indicated “no” to exposure to violence were directed to complete the demographics questionnaire, CTQ-SF and the DASS-21. The questionnaire required 15-20 minutes to fill in. Participants were qualified to enter a draw to win $50 each (4 prizes) Westfield gift cards by completing the survey. Participants interested in lucky draw were educated to click a link on completion of the survey. Entries to the draw were in no way associated to survey responses.

Results

During data cleaning, it was found that there was no age at exposure to violence, duration of exposure to violence or stigma values for participants who were not exposed to violence. Subsequently the age at violence exposure, duration, and stigma score was set to zero to prevent SPSS from removing the variable of violence as a constant. For the variable ‘Exposure to violence’, “Yes” response was coded as 1 and a “No” response was coded as 2. Data was assessed to note violations of the assumptions of linearity, singularity, and homoscedasticity. Although the independent variables were highly correlated with each other (Refer to Table 3), the VIF and tolerance statistics were within an acceptable range thus the assumption of multicollinearity was subsequently met. Assumptions were not violated, kurtosis and skew values signifying normal distributions were noted.

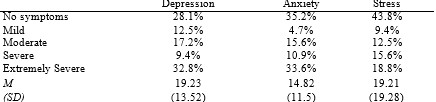

Levels of Depression, Anxiety and Stress experienced among South Asian Females are summarised in Table 1. Across the whole sample of those exposed to violence and not exposed to violence, the levels of depression, anxiety and stress were scored according to Lovibond et al. (1995) profile severity ratings.

Table 1

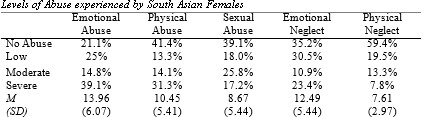

Levels of abuse experienced by South Asian females are summarized in Table 2. Across the whole sample of those exposed to violence and not exposed to violence, the levels of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, also neglect of emotional and physical nature were scored according to Bernstein et al. (2003) severity classification categories.

Table 2

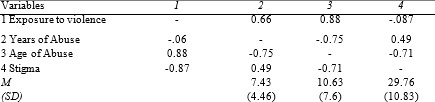

Descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 3 (see below). Calculations of means and standard deviations were performed for all independent variables. The number of participants exposed to violence was N=80 which reflects approximately 62.5% of participants. The participants mean age of abuse was 7.43 years (M=7.43, SD=4.5), which reflects that participants on average were exposed to violence around 7 years of age. The mean years of abuse was (M=10.63, SD=7.6), which reflects that on average this sample of participants were exposed to violence for up to 10 years. The average level of stigma (M=29.76, SD=10.83), reflects those participants experienced moderate levels of perceived stigma related to exposure to violence according to Gibson et al. (2001) severity profile rating scale. The correlations among the independent variables summarized in Table 3. All correlations were found to be significant.

Table 3

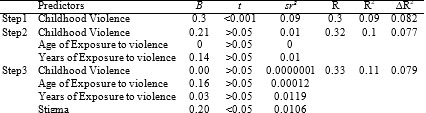

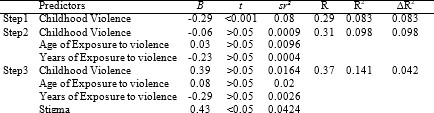

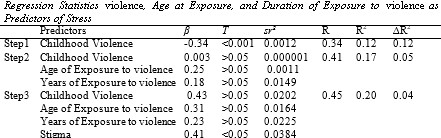

Three hierarchical regressions were performed with depression, anxiety and stress and exposure to violence, age at exposure to violence, duration of exposure to violence and stigma. These hierarchical regressions had three stages. At Step One of the hierarchical regressions, the variable of exposure to violence was added. At Step Two, the variable of age at exposure to violence and the duration of exposure to violence were added. At Step Three, perceived stigma related to exposure to violence was added. Tables 4, 5 and 6 display the regression values for variables of depression, anxiety and stress, respectively.

Table 4

F(1, 117)= 11.831, p<0.01 and accounted for 8.2% of the variation in depression. Adding age at exposure to violence and the time length of exposure to violence in Step Two did not significantly change the model (p>0.05), however the model remained significant, F(3, 115)= 4.376, p<0.01. Adding stigma related to experiences of violence in Step Three did not significantly change the model (p>0.05), however the model remained significant, F(4,114)= 3.604, p<0.01. As neither of variables in Step Two or Step Three contributed significantly to the model, the most important predictor of depression was exposure to violence, accounting for 8.2% of the variation in depression.

Table 5

Table 5 depicts that violence was significantly associated, F (1,117) = 10.855, p<0.01 with anxiety and accounted for 7.5% of the variation in anxiety. Adding age at exposure to violence and the interval of exposure to violence in Step Two did not significantly change the model (p>0.05), however the model remained significant, F (3,115)= 4.285, p<0.01. Adding stigma related to experiences of violence in Step Three significantly changed the model (p<0.05), and the model remained significant, F(4,114)= 4.788,p<0.01. With all four of the dependent variables present in Step Three, only stigma was significant, which accounted for 4.2% of the variation in anxiety. All four of the variables (exposure to violence, Age at exposure to violence, Duration of exposure to violence and Stigma accounting for 11.1% of the variation in anxiety.

Table 6

Table 6, depicts that violence was significantly associated, F(1, 117)= 15.734, p<0.01 with stress and was responsible for 10.9% of the variation in stress. Adding the age at exposure to violence and the duration of exposure to violence in Step Two, significantly changed the model (p<0.05), and the model remained significant, F(3, 115)= 3.463, p<0.001. The model significantly changed (p<0.05) when stigma related to experiences of violence was added in Step 3, and the model remained significant, F(4,114)= 5.641, p<0.01. With all four of the dependent variables present in Step Three, only stigma was significant, which accounted for 3.8% of the variation in stress. All four of the variables explained 17.6% of the variation in stress.

Discussion

The findings are in line with the study’s hypothesis, indicating a strong association between exposure to violence during childhood and higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress experienced as an adult, among females of South Asian descent. Furthermore, the results support the study’s hypothesis, indicating that stigma associated with childhood experience of violence moderated the relationship among early exposure to violence and anxiety and stress experienced among South Asian female adults. The results further highlighted that stigma associated with exposure to violence during childhood was a stronger predictor of anxiety and stress among South Asian female adults. However, it is interesting to note that stigma associated with exposure to violence during childhood, was not found to be a moderator for depression, and only exposure to violence was found to be the most significant predictor for depression among South Asian female adults.

Consistent with past literature, the present findings indicate that among the participants with a past of juvenile exposure to violence, levels of depression, anxiety and stress were significantly higher as contrast to the participants never exposed to violence in childhood (Miller-Graff et al., 2015; Norman et al., 2012; Pico-Alfonsko et al., 2006, Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2005; Sanderson, 2006; Sternberg et al., 2006; Springer et al., 2007). This finding highlights that exposure to violence during childhood plays a noteworthy part in the development of depression, anxiety and stress in adults. In hierarchical regression model with the conjectured moderator stigma, exposure to violence during childhood was no longer the most significant predictor for higher levels of anxiety and stress. Instead, stigma significantly moderated the original association between exposure to violence during childhood and higher levels of anxiety and stress experienced as an adult. Overall, the results provide robust backing in examining stigma as a moderator between early exposure to violence and higher levels of anxiety and stress among South Asian female adults. This is the first study to examine whether one of the traumagenic dynamics (stigmatisation) moderates the relationship between exposure to violence during childhood and levels of depression, anxiety and stress experienced as an adult. The current findings align with prior research as well as past literature, which has found that stigma moderates the relationship between a history of exposure to specific genres of child abuse (e.g., sexual abuse) and adult psychopathology indications (Murray, et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2015; Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). This present research has extended these findings to the perception of stigma associated with the experience of childhood violence resulting in elevated degree of anxiety and stress. Consequently, the present research findings established how stigma might express a pliable point of therapeutic intervention across two distinct forms of psychological distress. However, perceived stigma was not found to be a moderating factor between exposure to violence during childhood, and levels of depression experienced as an adult. It is outside the room of this research to investigate the aspects behind this finding.

The findings of the present research indicated that 66.2% of the sample testified experiencing violence in early years of their life. However, this figure needs to be considered with caution as within South Asian communities, empirical evidence supports that stigma may hinder women from unveiling violence to others (Ayyub, 2000). This is due to factors associated with stigma including fear of rejection and social isolation within South Asian communities (Ahmad et al., 2004). Moreover, South Asian women tend to minimise and deny abuse in order to protect their image and the image of their families (Dasgupta & Warrier,1996). Additionally, Ahmad et al. (2004) studied the affiliation between patriarchal belief and perception of violence in South Asian females’s found that 52.6 % of South Asian females (with higher agreement of patriarchal social norms) were associated with not being able to identify that the vignette depicted a violence victim, despite it being clearly indicated. In the Australian context alone, according to the Forsyth (2016), women who had identified themselves as having experienced violence had not reported it, due to perceiving the incident as minor in nature and/or out of shame and guilt, two concepts of which constitute stigma. Thus, victims are often reluctant to report exposure to violence due to perceived stigma and may also lack the capacity to acknowledge that what they have endured is considered violence. This may explain the results of our study whereby participants’ who had indicated not being exposed to violence, had recorded responses on the CTQ-SF pointing in the direction of experiencing varying forms of abuse in the present study. Consequently, within South Asian communities, violence experienced during childhood continues to remain masked and unreported because of the stigma that inhibits women from disclosing their abuse (Pinheiro, 2006). Thus, violence needs to be acknowledged among South Asian and similar communities, in order to increase help seeking behavior and recovery as well as to reduce the detrimental long-term mental health concerns for woman and children.

Age at exposure to violence and duration of exposure to violence have been examined as moderators of the relationship between childhood exposure to violence and adult mental health consequences (Sternberg et al., 2006). Consistent with Sternberg et al. (2006) meta-analysis findings, age and duration of exposure were not found to be potential moderators. The findings of the present study depict that, average age at exposure to violence was 7 years of age. However other studies have shown that violence occurs even before birth of the child or begins earliest period of life (Macy et al., 2007). Thus, the present findings could be attributed to recall bias around the age at which exposure occurred. Wells, Morrison and Conway (2014) also suggest that adults are incapable to recall detailed recollections before the age of 7 years, which may explain the present research findings. The literature further highlights that violence generally lasts an average of 10 years (Graham- Bermann et al., 2007; Lindhorst & Beadnell, 2011) and the longer the duration of exposure to childhood abuse, the higher the probability of developing emotional disorders (Miller-Graff et al., 2015). In line with past literature, the present research findings indicated that the average duration of exposure to violence was 10.63 years of age. However, it is imperative to note that recalling childhood experiences of exposure to violence requires close examination due to recall bias and potential under reporting.

LimitationsThe retrospective report of exposure to violence during childhood could have been influenced by recall bias. This may result in our findings of the reported age at exposure to violence being earlier and reported duration of exposure to violence being briefer in duration compared to reality. It is also important to consider that the self-reports measure may not provide an accurate representation of traumatic experiences and have inherent potential biases due to subjectivity. Participants may have also answered in the negative to questions seemingly intrusive, and the sample may or may not have similar cognitions surrounding what may constitute as violence, which possibly will lead to misjudge prevalence rates.

In the study, the participants’ mean responses on measures of depression, anxiety and stress surpassed the extremely severe range. However, it is not clear as to whether these participants would have other stressors impinging on them at the time of filling in the survey or on an ongoing basis. Furthermore, other childhood stressors, such as parental substance abuse, or coming from dysfunctional families, could also have contributed to adult mental health concerns. Moreover, based on the sample of participants, the females who came forward to participate are likely to have been better able to cope.

Lastly, the sample is not essentially representative of all South Asian women in Australia. A large number of South Asian diaspora (such as Indian Caribbeans) were not captured by this study. It is also important to ponder that the major chunk of the sample was of Srilankan descent and as a result, this study did not have an equal representation of the diverse South Asian groups.

Conclusion and Implications ReferencesThis research adds to the existing literature on the detrimental long-term effects of childhood exposure to violence and signs of depression, anxiety and stress experienced as an adult among South Asian females. The present research also emphasizes the role of stigma in moderating the association between childhood exposure to violence and experiences of anxiety and stress during adulthood, in this population group within Australia. Future research is required to unravel coping methods such as disengagement associated with the upkeep of symptoms such as depression, anxiety and stress over time to develop an increased understanding of this association. Moreover, research is needed to investigate methods in which early intervention could target stigma and assist survivors in their recovery as well as means of prevention. In conjunction with prevention, strategies need to be implemented that can address factors that moderate the impact caused by exposure to violence during childhood and long-term mental health concerns. The present study has been a step in this direction by examining the role of stigma as a moderator between exposure to violence and adult symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. The results directed towards the need to elevate awareness of the impact of childhood exposure to violence on adults, specifically within the South Asian communities. Moreover, the findings of the current study reinforce the need for using a developmental lens and having a culturally sensitive understanding in the assessment and treatment of mental health concerns, especially in the context of working with vulnerable members of the society, including South Asian women and children with suspected histories of exposure to violence.

ReferencesAustralian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Personal Safety Survey 2016, cat. no. 4906.0. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4906.0

Ahmad, F., Riaz, S., Barata, P., & Stewart, D. E. (2004). Patriarchal beliefs and perceptions of abuse among South Asian immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 10(3), 262-282. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203256000

Ayyub, R. (2000). Domestic violence in the South Asian Muslim immigrant population in the United States. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 9(3), 237-248. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009412119016

Barn, R., & Sidhu, K. (2002). Dealing with difference: professional conceptualisations of health and social care needs of Bangladeshi women in London. Journal of Social Work Research and Evaluation, 3(2), 145-158. Retrieved from https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/dealing-with-difference-professional-conceptualisations-of-health-and-social-care-needs-of-bangladeshi-women-in-london(529b1ed1-881a-4506-8be8-306981ba3448).html

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., ... & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169-190. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Byrne, P. (2000). Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6, 65-72. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/apt.6.1.65

Campo, M. (2015). Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence. Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia (CFCA), Australian Institute of Family Studies. http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1759.1121

Coffey, P., Leitenberg, H., Henning, K., Turner, T., & Bennett, R. T. (1996). Mediators of the long-term impact of child sexual abuse: Perceived stigma, betrayal, powerlessness, and self-blame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(5), 447-455. http://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(96)00019-1

Dasgupta, S. D., & Warrier, S. (1996). In the footsteps of “Arundhati” Asian Indian women's experience of domestic violence in the United States. Violence Against Women, 2(3), 238-259. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077801296002003002

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 614-621. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42

Forsyth, L. (2016). The cost of violence against women and their children in Australia [Ebook].Sydney:KPMG.Retrievedfrom: https://www.dss.gov.au/ Gibson, L. E., & Leitenberg, H. (2001). The impact of child sexual abuse and stigma on methods of coping with sexual assault among undergraduate women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(10), 1343-1361. http://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00279-4