Pubertal Changes and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Body Image Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Girls

Shumaila Tasleem*, Tazvin Ijaz, & Rabia Iftikhar

Government College University, Lahore

The current study was designed to investigate the relationship of pubertal changes experiences with psycho-social factors in adolescent girls of Pakistan. A cross sectional study design was used to conduct this research. A large sample of adolescent girls (N=906) was selected from public and private Schools. All girls were selected from grade 7th, 8th and 9th through stratified random sampling. Data Collection was done in the months of April, 2018- May, 2019. Pubertal Changes Experience Scale (Tasleem et al., 2020), Mental Health Inventory (Bashir & Naz, 2013), Body Dissatisfaction Scale (Tariq & Ijaz, 2015), Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Frick, 1991) were used in the data collection process. The hypothesis testing was done through Pearson Product Moment Correlation and Mediation. A positive correlation between emotional distress at the time of puberty, body dissatisfaction and psychological distress was found. Moreover, emotional distress has inverse correlation with psychological wellbeing of adolescent girls. Body image dissatisfaction was significantly positively correlated with psychological distress and negatively correlated with psychological well-being. The factor of body image dissatisfaction emerged as a mediating variable between pubertal changes experiences and mental health of adolescent girls. It is also established in the study that pubertal changes influence social role of adolescent girls and psychological distress. The current study provided an empirical evidence about emergence of body dissatisfaction as a mediating factor between negative pubertal experiences and mental health of adolescent girls at the time of puberty.

Keywords: puberty; mental health; adolescent girls; body image

Pubertal development culminates in physical maturity; this development renders a unique experience often associated with increased psychological distress stemming from body image, parental-child relationship, and academic performance (Khan, 2003). Pubertal changes are often associated with hormonal shift in body that cause psychological disturbance. It is reported that adolescent girls experience heightened emotional distress including low mood, irritability and crying at the time of puberty (Reynold & Juvonen, 2011) which is 2 to 4 years duration after onset and arise with general physical changes that include skeletal and sexual changes such as secondary sexual characteristics reproductive competence etc. (Rogol et al., 2002). In female adolescents, early experience of menarche is different than later occurrences and impacts how girls cope with middle school and peer pressure (Lee et al., 2013).

Adolescence is a vital period in human development. Thus, it needs to be explored by all means to understand the exuberance of this developmental period. However, the onset of puberty which is a milestone of adolescence is critical to understand. The bracket of age range, which is established in WHO (10-19) is wide enough that cannot encapsulate the needs and realities of 10 years old and 19 years old (Aangan, 2001), despite these limitations, the age parameters of adolescence encircle a general period of change from childhood to adulthood and has its unique qualities (Durrant & Sather, 2000). Adolescent girls in Pakistan are facing the same reproductive health issues as the adult population, particularly women. According to reports by USAID adolescent girls are still facing gender differences that place girls and boys on separate roles of life regarding education, job predictions, labor force, reproduction and duties in household activities (Aahung, 2001).

The onset of menstruation is the commencement period of female adolescences. Pubertal changes can intensify anxiety where vulnerable population can experience panic attack, social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Edward, et al. (2011) reported that environmental influences moderate pubertal changes and depressive symptoms. In addition, social and emotional influence increase risk of mental health difficulties in adolescents (Reena, 2015). This investigator reported other behavioral changes in adolescent girls (7-9 graders) which included changes in sleep patterns, lack of concentration in work, anger and irritation in routine life work are also reported to prevail in adolescent girls during the time of puberty (Sinha, 2012). To avoid such changes and problems the author suggested, that mothers of these adolescents should be socially aware, and should have knowledge and demands in puberty, and also need to guide their girls towards positive emotional development and their well-being. Such problems are reported in American (Achenbach & Mcconaughy, 2003) and English (Collishaw et al., 2004) cultures.

Pubertal changes among girls is the most un-researched area, especially in our country. So, the current study aimed to highlight the most critical construct of female development. Although body image dissatisfaction has an impact on psychological welfare at various stages of a lifetime, and during adolescence this relation is the strongest (Carroll et al., 1999; Frisen et al., 2009). Unhappiness with body shapes is related to clinical depressive symptoms reported within adolescent clinical populations. Other clinical disorders including anorexia nervosa and bulimia are also common at the time of puberty (Bulik et al., 2001). On the other hand, adolescent population which is non-clinical showed lower self-esteem, more anxiety disorders and depression than other peers. This relationship of body dissatisfaction and psychological distress is often linked to subjective (peer or social comments) assessment appearance. Body image and physical appeal remain comparatively constant across early adolescence, but becomes significant during the age of 15-18 years because of pubertal changes which occur at that time (Rosenblum & Lewis, 2003).

The current situation of social networking and undue concerns of social approval regarding body image is persisting in young females. Excessive media use is found to be a strong predictor of BID in adolescent girls and ratio is higher in urban population as compared to rural population (Bilal et al., 2021). This study helped to estimate a magnitude of problems related to pubertal changes and its correlates. As the present trends in psychological research are more focused on cross cultural manifestation of the phenomenon, therefore the foremost concern of the current study is to explore indigenous construct of pubertal changes experiences and BID in our culture. The present study explored the relationship of pubertal changes experiences with mental health problems and BID in adolescent girls. Effective parenting was one of the most interrelated variables during pubertal development. So, the relationship of effective parenting and puberty experience in girls was also established in this study.

Method

A sample consisted of 906 adolescent girls, was collected through stratified random sampling at female schools (government and private) Lahore, Pakistan. The age range of the sample was 11-18 years (M = 13.68, SD = 1.71). Two strata based on the sectors and grades (7-9) were selected and students were randomly from each stratum. Menstruating female students were included in the study and others excluded. Only 29.9 % of the sample reported having prior information about menstruation while 70% girls were not prior informed about menstruation. Among the sample 23.7% adolescent girls reported positive reaction towards onset of menarche, whereas 73.3% girls reported negative reaction towards onset of menarche. On the contrary 76.7 % girls reported a positive family reaction towards onset of menarche. Mostly girls (93.5 %) reported guidelines were available after the onset of menstruation and their first informant was reported to be the mother or sister (84.0 %).

Assessment Measures

Pubertal Changes Experience Scale

The PCES is a self-report measure in Urdu language to investigate pubertal experiences of adolescent girls. The scale is developed by Tasleem et al. (2020). The scale has 26 items with 5- point Likert scale ranging from absolutely wrong (1) to absolutely right (5). There are three subscales including emotional distress (10 items), behavioral maturation (11 item) and self-care and management (5 item). Concurrent validity (r = .16) and test re-test reliability (r = .80) and alpha coefficient of this scale is (r = .82) (Tasleem, et al., 2020).

Body Dissatisfaction Scale

Body Dissatisfaction Scale (Tariq & Ijaz, 2015) is an indigenously developed scale in Urdu on Pakistani population. This scale has 26 items which has been used in current study with a value .85. Test Re-test reliability is reported to be .92 which is quite high and concurrent validity is .72 for women version. This scale has been used in the current study by obtaining permission from the author.

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire

The APQ consists of 42 items in the form. Five domains of effective parenting are included in the scale. These domains are positive involvement (10 items), monitoring and supervision (10 items), positive parenting (6 items), inconsistent discipline (6 items) and corporal punishment (3 items). This scale has adequate and established psychometric properties (Frick, 1991). It has differentiating criteria between clinical and non-clinical population. Urdu version of APQ has been used in the study. The translated version also has similar number of items with established reliability, established a value of APQ is .82 for ample of current study.

Mental Health Inventory

The MHI assesses mental health problems in adolescent girls (Veit & Ware, 1983). Translated and adapted in Urdu (Bashir & Naz, 2013) and used in other studies (Bano & Malik, 2013: Mahmood & Malik, 2013). The inventory presents an overall picture using a mental health index. On the other hand, it has two major subscales including psychological well-being (a = .79) and psychological distress (a = .83) among individuals. This scale is reported to be valid and reliable with high alpha coefficient (Mahmood & Malik, 2013).

Demographic Form

On a demographic sheet various characteristics of participants such as age, class, age at menarche, prior information, and family reaction towards menstruation, first informant, and parent’s education birth order etc. were documented. All the instruments were used with the permissions of their concerned authors.

Procedure

This study uses a cross-sectional design to establish relationships between pubertal changes and mental health mediated by BID and parenting. Written and oral informed consent from school administration and parents of the participants were taken. Keeping the sensitivity of the topic in mind confidentiality was assured and participants were debriefed after each data collection session. The data was collected in classrooms in groups. It took 35 to 40 minutes to complete all scales. Participants were debriefed at the end of data collection and thanked for their participation.

Results

Relationships among demographic characteristics, experiences that result from

pubertal changes, effective parenting, body dissatisfaction and mental health Pearson Product Moment correlations were carried out (see Table 1). Results show parental education was significantly and positively correlated with emotional distress and psychological well-being, while showing inverse relationship with behavioral maturation and body dissatisfaction. Effective parenting by the mother was significantly positively associated with behavioral maturation, self-care and psychological wellbeing.

Table 1

Correlation between Pubertal Changes Experience, Body Dissatisfaction and Mental Health (N=906)

|

Variable |

Age |

MA |

ME |

FE |

MP |

FP |

ED |

BM |

SM |

BD |

PD |

PW |

|

Age |

- |

.41*** |

-.17*** |

-.17*** |

.05 |

.03 |

-.01 |

.06 |

-.01 |

.08* |

.09** |

-.02 |

|

Menorrheal Age (MA) |

|

- |

-.13*** |

-.13*** |

.06 |

.04 |

.06 |

.01 |

-.04 |

.05 |

.01 |

.01 |

|

Mother Education (ME) |

|

|

- |

.55*** |

-.01 |

-.02 |

.15** |

-.16** |

-.03 |

-.08** |

-.01 |

.06* |

|

Father Education (FE) |

|

|

|

- |

-.01 |

.04 |

.15*** |

-.17*** |

-.02 |

-.08* |

-.01 |

.10** |

|

Mother Parenting (MP) |

|

|

|

|

- |

.76*** |

-.03 |

.14*** |

.08** |

.02 |

.02 |

.21*** |

|

Father Parenting (FP) |

|

|

|

|

|

- |

-.01 |

.08** |

.10** |

.06* |

-.01 |

.17*** |

|

Emotional Distress (ED) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

-.29*** |

-.26*** |

.23*** |

.34*** |

-.24*** |

|

Behavioral Maturation (BM) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.29*** |

.03 |

-.11** |

.03 |

|

Self-care and Management (SM) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.06 |

-.11* |

.01 |

|

Body Dissatisfaction (BD) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.29*** |

-.20*** |

|

Psychological Distress (PD) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

-.12*** |

|

Psychological Wellbeing (PW) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Effective paternal (father) parenting was significantly and positively correlated with behavioral maturation, self-care, body dissatisfaction and psychological wellbeing. Likewise, emotional distress has significantly positive association with pessimism, body dissatisfaction and psychological distress. Whereas body dissatisfaction was found to be significantly positively correlated with psychological distress and negatively correlated with psychological wellbeing. The overall picture of correlation analysis depicted pubertal changes experiences are related with psychosocial attributes of adolescence that lead them towards psychological distress and presence of positive attributes like behavioral maturation and self-care lead them towards psychological wellbeing.

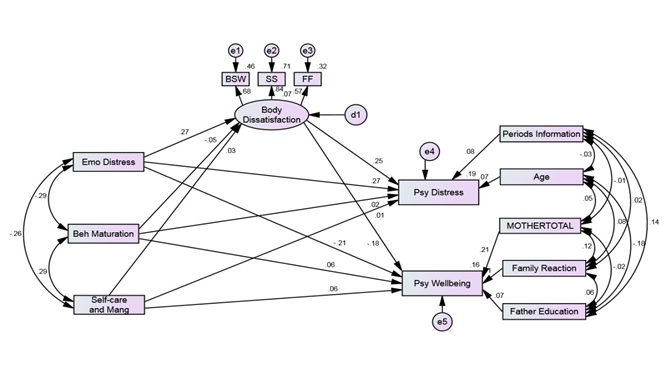

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was done to test the hypothesis that body dissatisfaction would mediate between pubertal changes experience (emotional Distress, behavioral maturation and self-care) and mental health problems in adolescent girls. Effective parenting score, and few demographic variables were studied as controlled variables in the analysis to see the mediating role of body dissatisfaction on mental health of adolescent girls. Model fit is presented in table 2.

The absolute fit for the presented model was χ2 (65, 906) = 273.25, p < .05 and was not that good fit as per the standard criteria of the descriptive measure of fit. According to

Arbuckle (2012), value for modification indices for error covariance should be 4.0. To fit the model with covariance measures 7.0 or greater the analysis revealed RMSEA and SRMR

were .06 and .06 whereas the GFI, CFI and NNFI values were .96, .86, .85 respectively. These indices were appropriate enough to generalize the model on the tested data (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Empirical Results from a Complex Multivariate Model Representing Standardized Regression Coefficients.

Note. BSW (body weight), SS (skeletal structure), FF (facial features)

Table 2

Direct Effects of Emotional Distress, behavioral Maturation and Self-care and Management on Body Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress and Psychological Wellbeing

|

Variable |

Body Dissatisfaction |

Psychological Distress |

Psychological Wellbeing |

|||

|

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

Β |

SE |

|

|

Emotional Distress |

.27*** |

0.04 |

.26** |

0.04 |

-.21*** |

0.04 |

|

Behavioral Maturation |

-.05 |

0.04 |

.02 |

0.03 |

.06 |

0.03 |

|

Self-Care and Management |

.03 |

0.04 |

.01 |

0.03 |

.06 |

0.03 |

|

Body Dissatisfaction |

|

|

.25*** |

0.04 |

-.18*** |

0.04 |

*** p<.001

The results of direct effect showed that emotional distress significantly and positively predicted body dissatisfaction and psychological distress. However, emotional distress was a significant negative predictor of psychological wellbeing. Body dissatisfaction as expected was a significant positive predictor of psychological distress, and significantly negatively predicted psychological wellbeing. Behavioral maturation and self-care and management were non-significant predictors of body dissatisfaction, psychological distress and psychological wellbeing.

Table 3

Indirect or Mediation Effects through Body Dissatisfaction between Pubertal Changes Experience and Psychological Distress and Psychological Wellbeing

|

Variable |

Psychological Distress |

|

Psychological Wellbeing |

||

|

β |

SE |

|

Β |

SE |

|

|

Emotional Distress |

.07*** |

0.01 |

|

-.05*** |

0.01 |

|

Behavioral Maturation |

-.01 |

0.01 |

|

.01 |

0.01 |

|

Self-Care and Management |

.01 |

0.01 |

|

-.01 |

0.01 |

***p<.001.

Body dissatisfaction significantly positively mediated between emotional and psychological distress and inversely between emotional distress and psychological wellbeing during pubertal changes in adolescent girls (Table 3).

Discussion

Puberty is a critical bio psychosocial event which has long term consequences for adolescents' behaviors and well-being. Pubertal changes bring developmental and cognitive maturity, which as a result shape behaviors and relationship of significant others with adolescents (Grower et al., 2019). Psychological functioning of individual is very much dogged whether the challenges of adolescence are successfully met or not. It’s an established fact which is reported in 1998, despite a huge number of adolescent (9 million: age range 10-14 and 6.5 million: 15-19 years), research related to adolescents’ reproductive health is limited and reason is social taboo and restricted discussion about puberty. The current study attempted to highlight pubertal changes experiences and associated BID in adolescent girls. Mental health is also tested in the relation of experiences of pubescent variations in girls. Positive experience of pubertal changes of girls is significantly correlated with domains of mental health (Edward et al., 2011) These findings are in line with reported literature that incidence of pubertal changes is associated with depressive symptoms emerge in in adolescence (Cherry, 2019).

The role of the secure attachment resulted in family connectedness and facilitates adolescents for their self-regulation, autonomous and curious behaviors (Hill & Holmback, 1986). The inferences drawn in the present study confirmed the notion of effective parenting (aspects of positive and negative parenting) measured by APQ (Flicker, 1999) played positive role at the time of experiencing pubertal changes in adolescent girls. The findings also confirmed with the literature that put forward the notion of parental interaction as strong enough to mend adolescents’ mental script of future relationships (Simpson et al., 2007; Meeus & Nijs, 2007).

Emotional distress at the time of puberty in adolescent girls found as significantly positive correlated with body image dissatisfaction. The changes in body experienced by girls specifically at the time of puberty, make this period more sensitive for disturbance in body image of girls (Feingold & Mazzella, 1998). In correlation analysis of the current study, it is suggested that emotional distress after attaining puberty led to increase body image dissatisfaction. Existing literature proved a concern about increased prevalence of body image, yet the correlational aspect of body image and broad aspects of young people’s life is needed. In a systematic study, Davison and McCabe, (2006) investigated a positive relationship between body image and peer relationship and psychosocial functioning of adolescents. Moreover, there are gender difference were reported in context of poor self-worth of girls compared to boys correlated with body image in same aged adolescence. The outcomes of the current study are also confirmed body dissatisfaction at the time of pubertal changes. Whereas the positive experience at the time of puberty (Behavior maturation and self-care) established in current study appeared to be protective factors against body dissatisfaction.

Onset of pubertal changes is often related to depressive symptoms or psychological distress in adolescence. Psychological well-being and psychological distress are found to be positively correlated with experiences of pubescent girls which is in line with the existing literature (Jones, 2004; Wertheim et al., 2009). Maturity in girls at the time of puberty and their self-care resulted in psychological well-being, while the same dimensions were found to be inversely correlated with psychological distress. Environmental influences including divorce of parents, loss, death or separation of loved one or any prolonged illness which become the indicators of depression symptoms, and which are moderated by the pubertal changes at the same time (Edward et al., 2011).

As a result of indigenous scale development, dimensions of PCES for instance behavioral maturation and self-care and management were emerged (Tasleem et al., 2020). Hence, it is further tested to establish relationship of pubertal changes experiences and body dissatisfaction among adolescent girls in Pakistan. Social cognition and structural development of brain networks connected in social processing is associated with attaining adolescence goals successfully (Care about others, altruistic behaviors and react to peer etc.) (Blakemore, 2008). Furthermore, research also conclude that pubescent also demonstrate increased motivation to become influential to the peers, to get attention and to become more socially approved they become responsible and mature (Gogtay et al., 2004; Keating & Robertson, 2004), present study also confirmed behavioral maturity in consequence of puberty in Pakistani adolescent girls. Attainment of behavior maturation and self-care domain as a result of pubertal changes is a major contribution of present study that is highlighted the positive domains as a result of puberty. Although these examples provide an appealing role of pubertal maturation in context of social development and later adult behaviors, but still empirical research on the influence of puberty on social development of adolescents needs extended investigation. Summarizing the current review of influential role of pubertal changes on the behavioral indication is established.

The mediating role of body dissatisfaction between pubertal changes experiences and mental health was established through structural equation modeling (SEM). Since the results of the direct effect showed that emotional distress caused by pubertal changes was significant positive predictor of body dissatisfaction and psychological distress. Body dissatisfaction is at a high level during adolescence due to physical changes associated with puberty (Abraham & O’Dea, 2001). Many studies concluded that increased body dissatisfaction at the time of adolescence is frequently reported because of social variables which are standards of ideal body, socio economic status and messages from media and friends’ reaction towards individuals and sometimes peer pressure to look thin (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001). The current study endorsed body dissatisfaction as a negative predictor of psychological distress in adolescent girls experienced at the time of puberty. Furthermore, the present study also confirmed the inferences of existing literature that conclude that gaining weight as a result of pubertal changes leads to increased body dissatisfaction regarding size and shape of body in girls (Presnell et al., 2004).

The results assimilated through structural relationship for pubertal changes experience, body dissatisfaction and mental health were derived after controlling few variables including, effective parenting (by mother and father), age, prior information about menstruation, family reaction about menstruation and education of the father. Controlled variables served as measures that remain constant and observed carefully with dependent variable to measure the effect of exogenous variable on endogenous variable (Shuttleworth, 2008). There is also an effect on dependent variable but that effect remained constant in statistical analysis.

The results of indirect effect showed that body dissatisfaction was found to be a significant positive mediator between pubertal changes experience and psychological distress. This showed that, increase in emotional distress (while experiencing puberty) tends to increase body dissatisfaction and increase in body dissatisfaction in turn increases psychological distress. Likewise, heightened emotional distress predicts decrease in psychological well-being while mediated through body dissatisfaction. Self-perception of adolescents about body dissatisfaction becomes highly pertinent and usually associated with negative psychological functioning, such as low self-esteem and depression (Choi & Choi, 2016).

Implications

This study will provide a doorway to describe emotive and interactive changes which occur with the emergence of puberty. These physical and body changes are compulsory to be shared with adolescents in reference of their future adult life. It is important to spread the word about awareness about pubertal changes, hygienic conditions and healthy womanhood. So, it might be concluded that the current study addressed a very communal yet significant phenomenon, and provided a basis to explore more about developmental construct. The findings of the current study provided baseline information that can be shared by the school teachers as firsthand empirical evidence regarding pubertal changes experiences of adolescent girls.

Limitations and Suggestions

Despite the best efforts to ensure the best prospect of study, still it has some limitations. Since the study is based on school going girls, this study can be further extended to a comparison of rural and urban areas which could also result in some meaningful findings.

The pubertal changes experiences are studied only in girls’ population; it is a matter of equal importance for both girls and boys. So, it is suggested that pubertal changes in boys should be explored and identify their developmental journey. This will provide a gender-based comparison also regarding pubertal changes.

Finally, few intervention or training programs are highly recommended for adolescents. Such youth development programs are recommended that train adolescent about life skills and lead them to adjust their most important phase of human development.

References

Aahung. (2001). Seeing Change, A Report of Training of Trainers Aware for Life (Adolescents). Retrieved from Department of Women’s Development and Social Welfare, and UNICEF.

Aangan. (2000). Mother’s Views about Child Sexual Abuse. Islamabad: Rozan.

Abraham, S. & O'Dea, J. (2001). Body mass index, menarche and perception if dieting among peri-pubertal adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200101)29:13.3.CO;2-Q

Achenbach, T. & Mcconaughy, S. (2003). The Achenbach system of empirically based assessment. Handbook of Psychological and Educational Assessment of Children: Personality, Behavior, and Context, 2, 406-432.

Aflaq, F. & Jami, H. (2012). Experiences and attitude related to menstruation among female students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 27, (2), 201-224.

Al-Subaie, A. (2000). Some correlates of dieting behavior in Saudi schoolgirls. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 242-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200009)28:23.0.CO;2-Z.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2012). IBM. SPSS. AMOS. User’s Guide. IBM Corp.

Arian, A. (2003). Israeli public opinion on national security 2004. Tel Aviv: Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies.

Bano, S., & Malik, F. (2013). Domestic violence, psychological distress and depression among women in shelter homes (unpublished master’s dissertation). Clinical Psychology Unit, GCU, Lahore.

Blakemore, S. J. (2008). The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews, Neuroscience, 9,267–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2353.

Bashir, U. & Naz, M, A. (2013). Attitudes and barriers towards seeking professional help for mental health issues in Pakistan: A cultural perspective (unpublished master dissertation). Clinical Psychology Unit, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan.

Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.179

Cherry, K. (2019). “Why Are Statistics Necessary in Psychology?” Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/why-are-statistics-necessary-in-psychology-2795146

Choi, E., & Choi, I. (2016). The associations between body dissatisfaction, body figure, self-esteem, and depressed mood in adolescents in the United States and Korea: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 249-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.007

Collishaw, S., Maughan, B., Goodman, R., & Pickles, A. (2004). Time trends in adolescent mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(8), 1350-1362

Deater-Deckard, K. (2001). Annotation: Recent research examining the role of peer relationships in the development of psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 565–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00753

Delfabbro, P., Winefield, T., Trainer, S., Dollard, M., Anderson, S., Metzer, J., & Hammerstrom, A. (2006). Peer and teacher bullying/vicitimization of South Australian secondary school students: Prevalence and psychosocial profiles. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904X24645

Durrant, V. L., & Sathar, A.Z. (2000). Greater Investments in Children through Women’s Empowerment: A Key to Demographic Change in Pakistan? (Working paper no.137). New York: Population Council.

Edwards, A. C., Rose, R. J., Kaprio, J., & Dick, D. M. (11). Pubertal development moderates the importance of environmental influences on depressive symptoms in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(10), 1383–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-0109617-3

Eapen. V., Mabrouk, A. & Bin-Othman, S. (2006). Disordered eating attitudes and symptomatology among adolescent girls in the United Arab Emirates. Eating Behaviors. 7, 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.07.001

Feingold, A., & Mazzella, R. (1998). Gender Differences in Body Image Are Increasing. Psychological Science, 9(3), 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00036

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Unpublished rating scale). University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Gogtay,N., Jay, N., Giedd, J.N., Lusk, L., Kiralee, M., Hayashi, K.M., Greenstein, A.D., Vaituzis,C., Nugent, F.T., David, H., Herman, D.H., Liv, S., Clasen, L.S., Arthur, W., Toga, A.W., Judith, L., Rapoport, J.L., & Thompson, P.M.(2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(21), 8174–8179. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101

Goodyer, I. M. (2001). Life events: Their nature and effects. In I. M. Goodyer (Ed.), Cambridge child and adolescent psychiatry. The depressed child and adolescent (p. 204–232). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511543821.009

Graber, J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Paikoff, R., & Warren, M. (1994). Prediction of Eating Problems: An 8-Year Study of Adolescent Girls. Developmental Psychology, 30, 823-834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.6.823.

Grower, P., L., Ward, L.M. & Beltz, A.M. (2019). Downstream consequences of pubertal timing for young women's body beliefs. Journal of Adolescence, 72, 162-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.02.012.

Hill, J. P., & Holmbeck, G. N. (1986). Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. In Whitehurst, G. J. (ed.), Annals of Child Development (Vol. 3). JAI Press, Greenwich, CN.

Jones, D. C. (2004). Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40, 823–835. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.823.

Keating, F. & Robertson, D. (2004). Fear, black people and mental illness: A vicious circle? Health & Social Care in the Community, 12,439-447. https://doi.10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00506.x

Khan, A. (2003). Adolescent Reproductive Health in Pakistan: Status, Policies, Programs and Issues. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25988.12164.

Kobak, R., Abbott, C., Zisk, A., & Bounoua, N. (2017). Adapting to the changing needs of adolescents: parenting practices and challenges to sensitive attunement. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.018

Lewis, V. & Devraj, S. (2010). Body image and women's mental health. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 25(2), 99-114.

Littleton, H.L., & Ollendick, T. (2003). Negative Body Image and Disordered Eating Behavior in Children and Adolescents: What Places Youth at Risk and How Can These Problems be Prevented? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022266017046

Mahmood, N., & Malik, F. (2013). Coping styles and mental health among mental health Professionals (unpublished master’s dissertation). Clinical Psychology Unit, GCU, Lahore.

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2001) . Parent, peer, and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence, 36 (142), 225-240.

Mousa, T.Y., Mashal, R.H., Al-Domi, H.A., Jibril, M.A. (2010). Body image dissatisfaction among adolescent schoolgirls in Jordan. Body Image, 7(1), 46-50. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.10.002.

Mrug, M., Zhou, J., Woo, Y., Cui, X., Szalai, A. J., Novak, J., Churchill, G.A., & Guay-Woodford, L.M., 2008). Overexpression of innate immune response genes in a model of recessive polycystic kidney disease. Kidney International, 73, 63-76.

Mumtaz, K., & Raouf, F. (1996). Woman to Woman: Transfer of Health and Reproductive Knowledge. Lahore: Shirkat Gah.

Pompili, M., Innamorati, M., Szanto, K., Di Vittorio, C., Conwell, Y., Lester, D., Tatarelli, R., Girardi, P., & Amore, M. (2011). Life events as precipitants of suicide attempts among first-time suicide attempters, repeaters, and non-attempters. Psychiatry Research, 186(2-3), 300-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.09.003.

Presnell, K., Bearman, S.K., & Stice, E. (2004). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 36(4): 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20045

Reena, M. (2015). Psychological Changes During Puberty - Adolescent School Girls. Universal Journal of Psychology, 3(3), 65 - 68. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujp.2015.030301.

Simpson, E.G. (in press). Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: A narrative review of bidirectional pathways. Adolescent Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00112-2.

Sinha, C. (2012). Factors Affecting Quality of Work Life: Empirical Evidence From Indian Organizations. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 1(11): 31-40

Shuttleworth, M. (2008).“Controlled Variables.” Retrieved from https://explorable.com/controlled-variables

Sontag, L.M., Graber, J.A., & Clemans, K.H. (2011). The Role of Peer Stress and Pubertal Timing on Symptoms of Psychopathology During Early Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1371-1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9620-8

Susman, E. J., & Dorn, L. D. (2009). Puberty: Its role in development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Individual bases of adolescent development (p. 116–151). US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001006

Susman, E. J., & Rogol, A. (2004). Puberty and psychological development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (p. 15–44). US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tasleem, S., Ijaz, T., & Iftikar, R. (2020). Development of self-report measure on pubertal changes for school going adolescent girls. Rawal Medical Journal, 45(1).

Tariq, M., & Ijaz, T. (2015). Development of body image scale for university students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 30, (2), 305-322.

Veit, C., & Ware, J. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and wellbeing in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 730-742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730.

Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S., & Blaney, S. (2009). Body image in girls. In L. Smolak & J. K. Thompson (Eds.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention and treatment (2nd ed., pp. 47–76). Washington: American Psycho- logical Association.

Wymbs, B.T., Pelham,W.E. Jr., Molina, B.S., Gnagy, E.M., Wilson, T.K., & Greenhouse, J.B. (2008). Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youth with ADHD. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 735-44.