Demographic Determinants of Sexual Harassment in Police Women

Mueen Abid*, Saima Riaz, and Maryam Riaz

University of Gujrat, Gujrat

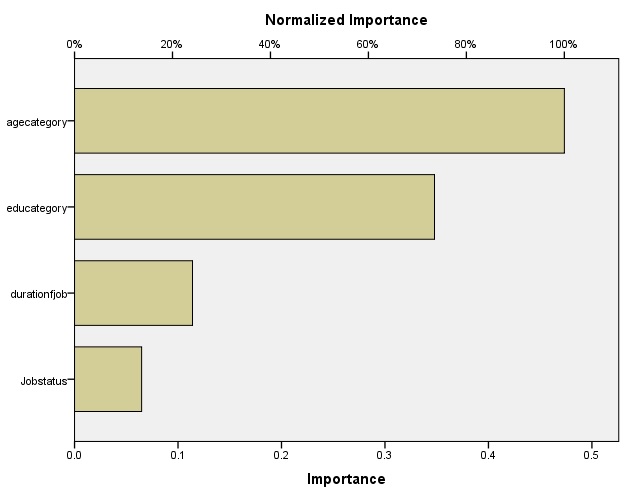

The present study aims at exploring the demographic determinants of sexual harassment in Police Women because this population is repressed and overlooked in exploring the sensitive issue of sexual harassment with particular reference to Pakistan. It was a cross-sectional research in which 191 police women personnel (age range = 15-65) were recruited from Gujrat and Gujranwala districts. A sexual harassment experience questionnaire was used to gauge sexual harassment (Kamal & Tariq, 1997). Information on various demographic characteristics was gathered using a self-made demographic sheet. Using SPSS 21, one-way ANOVA and neural network analysis were executed. The results of the present investigation demonstrated a substantial predictive relationship between demographic factors (job status, age, education, and duration of job) with sexual harassment. The results showed that age 0.473 (100% normalized importance) was the most significant predictor of sexual harassment among police women, followed by education 0.348 (73.5% normalized importance), duration of job 0.114 (24.1% normalized importance), and job status.065% (13.7% normalized importance). All four variables were contributing to the level of sexual harassment among police women. The results of the present investigation can be beneficial for policymakers in terms of new knowledge and statistical data to prevent this population from experiencing sexual assault.

Keywords: police women; demographic variables; sexual harassment; One-Way ANOVA; neural network analysis

Sexual harassment is characterized as unwelcome and offensive sexual irritation faced by people all over the world, but not discussed openly (Burn, 2019). World Health Organization (2012) reported that in several countries such as the former state union of Serbia and Montenegro, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Samoa, Brazil, Japan, Peru, Namibia, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania, approximately 1 in every 5 women may experience sexual harassment at the workplace, whereas every 3rd teenage girl experiences unwanted sexual behavior forcefully. Furthermore, it was identified that sexual harassment has adverse effects on mental and physical health of victims, and unfairly upsets and disturbs overall productivity of an institute by causing a devastating, violent and invasive work environment (Burn, 2019). Further, sexual provocation at any workplace is an obstacle in the way of achieving the organizational goal and stimulating a peaceful work environment for the workers (McCann, 2005). Sexual harassment is known to be a kind of gender discrimination, which runs counter to the idea that men and women should be treated equally (Numhauser-Henning & Laulom, 2012).

The House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee (2018) asserts that sexual harassment is intensely deep-rooted in our society and influences the survival of many innocent women and girls. Such types of sexual conduct are commonly committed in public places and male dominated professions such as public transportation, saloons, workplaces, gardens, and roads. It is a grave breach of human rights, values, and norms when working women and girls are subjected to sexual harassment and threats to their safety. To address the issue of violence against women, the governments of many nations have adopted a number of actions. A thorough examination and identification of the experiences of females who have experienced harassment, as well as its causes and repercussions on their psychological health, are essential parts of such an undertaking (Müller et al., 2007). Consequently, the purpose of the current study was to examine the sexual harassment experiences of women in the police department. This issue is overlooked and under-reported all over the world, especially in developing countries and particularly in Pakistan. Research looking at harassment among police officers found that female employees were subjected to higher incidents of harassment than their male colleagues (Lonsway et al., 2013; DeHaas et al., 2009; Somvadee & Morash, 2008; Thompson et al., 2006). These incidents included everything from simply being touched in a way that made someone feel uncomfortable, to being in close proximity to dirty jokes and stories, to being sexually attacked solely because one was a woman. Fitzgerald et al. (1999) postulated that many of the challenges women faced were not sexual in character, but rather stemmed from workplace prejudice towards them. According to Rabe-Hemp (2007) investigation and interviews with female law enforcement officers, 100 percent of them reported having been the victim of sexual harassment at some point during their employment. It's interesting to note that Rabe-Hemp (2007) went on to claim that women who transferred departments faced harassment in their new jobs.

In a similar manner, Burke and Mikkelsen (2004) investigated the fact that female police officers reported more sexual harassment occurrences, and those women who reported greater levels of sexual harassment also indicated lower job satisfaction. Sexual harassment, thus, has a detrimental impact on job satisfaction, retention, mental health, and physical health of the victims (DeHaas et al., 2009). Paludi (1996) and Kalof et al. (2001) have identified, that in police departments, females are more prone to sexual harassment, are more persuaded to tag even hidden types of sexual conduct, and their descriptions are typically broader than males.

Several studies have found that women who experienced sexual harassment faced a variety of negative outcomes, including lower job satisfaction, inferior physical and mental health, a lack of commitment to organisational goals, increased absenteeism, and a higher likelihood of abandoning their positions (Fitzgerald et al., 1997; Willness et al., 2007). Similar research was conducted by Zandonda (2011) on 160 working females from Nodla and Zambia's public and private workplaces to determine the prevalence and impact of sexual harassment. Their results indicated that 69% of respondents were reporting issues related to sexual harassment, and 75% employees claimed that there was no organizational policy to stop this harassing behavior. The results also showed that the victims' levels of stress and depression were clinically substantial. They expressed lower motivation levels and extremely poor psychological health.

Since sexual harassment prevails in workplaces, it is very significant and necessary to explore its determinants to concerned the complete picture. Various studies have explored critical part of socio-demographic characteristics in the prevalence of sexual harassment. Judicibus and McCabe (2001) examined the association between demographic characteristics and sexual harassment. Results showed that gender, age, and employee rank had a significant relationship with sexual harassment. They also found that female employees faced more sexual harassment related issues than male employees. Evidence disclosed that sexual harassment related problems are not limited to females, men also experienced such type of issues, however females were more likely than men to experience sexual violence (Konik & Cortina, 2008). Similarly, another study highlighted that participants having higher levels of education usually showed lower levels of sexual harassment, as their social influence increased with higher education (Nieminen et al., 2008). According to Schat et al (2006) examination into the predictive association between age and the crime, younger employees are more likely than older ones to experience sexual harassment at work. men are more likely to engage in sexual harassment. In addition, a study on the relationship between sexual harassment and age found a considerable negative correlation between the two. In other words, as the respondent's age increased, the severity of sexual harassment reduced (Ohse & Stockdale, 2008).

Sexual harassment related problems are not openly discussed and usually repressed. Due to the sensitivity of the topic, limited researches are conducted which indicates a great need to collect more empirical evidences (Pina et al., 2009). Despite the fact that sexual harassment is widespread in Pakistan, little research has been done in this area, particularly in relation to various workplaces. Statistics on sexual harassment of domestic employees are provided in a 2002 study by the AASHA (Association against Sexual Harassment). According to this study, approximately 80% of women workers in the nation are being sexually harassed in workplaces in both public organizations and private sectors (AASHA, 2002). Another phenomenological study was undertaken by Sadruddin (2013) to examine the prevalence of sexual harassment and its effects on victims in Pakistani workplaces. All of Karachi's public and private organisations that employed women made up the study's population. The sample of the study consisted of 200 females (N=200). The outcome indicates that sexual harassment is consistently experienced at the workplace in Pakistan and has impacted work performance and the overall wellbeing of females. Sexual harassment typically occurs in different forms such as verbal and physical exploitation, mental torture and intimidation. This is the major cause of prevalence of stress, depression and anxiety and other types of psychological ailment.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the predicted association between various demographic characteristics (age, education, job status and duration of job) with sexual harassment amongst police women. This study is highly noteworthy since it addresses the serious problem of sexual harassment of female police officers in Pakistani culture, which is typically suppressed and denied. Also, there is a significant research gap because very few studies have been done to investigate this issue in a prison situation. Exploring the prevalence of sexual harassment and its correlation with various demographic factors among female employees is very important in order to provide new knowledge and statistical information that will be useful to policy makers.

Method

The current study employed a cross-sectional study strategy to gather information and draw conclusions about a population of interest (universe) at a certain point. Cross-sectional studies have been characterized as snapshots of the population about which they collect information (Lavrakas, 2012). Sample of the study comprised 191 police women recruited from Gujrat and Gujranwala police departments, where, Gujrat and Gujranwala districts contained 78 (41%) and 113 (59%) working women respectively (age range = 15-65, mean age = 28.27, 40%, SD = 6.835). Census sampling technique was employed to select the study sample.

Table 1

Demographic Profile of Participants

|

Variable |

|

Categories |

Frequencies |

Percentage |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15-25 |

66 |

33.5% |

|

|

|

25-35 |

100 |

51% |

|

|

|

35-45 |

12 |

6.1% |

|

|

|

45-55 |

12 |

6.1% |

|

|

|

55-65 |

01 |

.5% |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metric |

56 |

28.6% |

|

|

|

Intermediate |

78 |

39.8% |

|

|

|

Bachelor |

45 |

23.5% |

|

|

|

Master |

10 |

5.1% |

|

Status of Job |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assistant Sub-Inspector |

01 |

.5% |

|

|

|

Head Constable |

19 |

9.7% |

|

|

|

Constable |

160 |

81.6% |

|

|

|

Sub-Inspector |

11 |

5.6% |

|

Duration of Job |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1-5 Year |

142 |

74.3% |

|

|

|

6-10 Year |

22 |

11.5% |

|

|

|

11-15 Year |

08 |

4.1 % |

|

|

|

16-20 Year |

07 |

3.6 % |

|

|

|

21-25 Year |

05 |

2.6 % |

|

|

|

26-30 Year |

03 |

1.5% |

|

|

|

31-35 Year |

04 |

2% |

Note. (N=191)

Table 1 specifies the frequencies and percentages of demographic features (age, education, job status and duration of job) of participants (N=191). It shows that most of the participants was between the ages of 25 and 35 years (f=100, %=51) and the rest of participants belonged to other above said age categories. With regards to education, most of the respondents (f=78, %=37.8) scored on intermediate level of education whereas, 45 respondents (23.5%) scored on bachelor level of education and 10 participants (5%) showed master level of education, respectively. Furthermore, 160 (81.6%) participants were working as a lady constable (LC) (160, 81.6%) 11 (5.6%) sub inspector, 19 (9.7%) as head constable and 1 (5%) as assistant sub inspector respectively. On the other hand, data related to categories of job duration illustrates that 142 participants are working in the police department between 1 to 5 year which is the lowest job duration, while 22 participants are working between 6 to 10 years, 08 participants are working between 11 to 15 years, 07 participants are working between 16 to 20 years, 05 participants are working between 21-25 years, 03 participants are working from 26-30 and 04 participants are working from 31-35 years (highest job duration category) respectively.

Assessment Measures

A demographic information sheet was adopted for data collection about age, education, job status and duration of job of police women. For the assessment of sexual harassment, Urdu version of sexual harassment experienced questionnaire was applied to identify the levels of the sexual harassment among female workers in police department, established by (Kamal & Tariq, 1997). It includes 35 items that assess the three dimensions of sexual harassment-related behaviors experienced by women in Pakistan at various workplaces (gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion). The Likert scale has four points, ranging from 1 to 4. The lowest level of sexual harassment was depicted by the participant’s score of 35 whereas the highest score was 140. The current study's scale has a high level of internal consistency, according to Cronbach's alpha value of.95. The author reported a reliability of.94.

Procedure

Due to the sensitive nature of the study, formal approval from the relevant authorities was acquired, and research participants completed an informed consent form. One demographical questionnaire and one standardized questionnaire were given to the respondents after outlining the nature and goal of the study. Each participant received the necessary instructions on how to complete the survey. They had the right to voice and transmit their ideas. Because sexual harassment is such a delicate subject, the respondents were given the assurance that their participation was voluntary and that any information gathered would be kept private and used exclusively for study. Respondents received thanks at the conclusion for their cooperation and involvement. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences was used to examine the data (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0). The study's analysis was divided into two sections: descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The information was compiled using descriptive statistics. Although inferential statistics like reliability analysis, neural network and one-way ANOVA was used to explore key findings. Neural network was implemented to check prediction, classification and importance of each demographic feature to determine sexual harassment. As Hastie et al. (2009) defined neural network as the most powerful and a common practice to identify complex predictive relationship and important classification of different constructs. Further, Neural Network analyses frequently reproduce outcomes in a unique way and recognize influential features not perceived by regression models (Beseler & Stallone, 2020). While Cronbach's alpha was computed to investigate the reliability of the sexual harassment experienced scale in the current study, one-way ANOVA was utilized to examine mean differences in different demographics on sexual harassment. As the study was approved by the Advanced Studies and Research Board (ASRB), University of Gujrat, Pakistan, this was taken into account when determining its ethical standing. The investigation considered every proposal made by the board. The police department officials whose samples were to be drawn had to provide their permission. The purpose, significance, and importance of the study were explained to the respondents. In addition, participants received assurances that they had the freedom to quit the study process whenever they wanted to without fear. Data privacy and confidentiality were also guaranteed to participants.

Results

Table 2 shows the Cronbach alpha calculated for sexual harassment experienced questionnaire.

Table 2

Reliability of Sexual Harassment Experienced Questionnaire

|

Measurement |

No of Items |

Cronbach’s Alpha Scores |

Kurtosis |

Skewness |

|

Sexual Harassment Experienced Questionnaire |

35

|

.78 |

-.818

|

.015

|

Note. (N=191)

Cronbach's alpha was calculated to determine the scale's reliability. High internal consistency of scale was found in the current investigation with reliability ratings of.78.

Table 3

Cronbach’s Alpha of Subscales of Sexual Harassment Experienced Questionnaire

|

Subscales |

Cronbach’s Alpha Scores |

Intercorrelation |

|

Gender Harassment |

.62 |

.56 |

|

Unwanted Sexual Attention |

.57 |

.44 |

|

Sexual Coercion |

.69 |

.57 |

Note. (N=191)

The above table represented Cronbach’s Alpha Scores and inter-correlation of three subscales of the sexual harassment experienced questionnaire. Results revealed the high inter-correlation of subscales in the current study.

Table 4

Model Summary

|

Cross Entropy Error |

Percent Incorrect Predictions |

||

|

Training |

Testing |

Training |

Testing |

|

74.333 |

31.400 |

21.3% |

21.0% |

Note. (N=191)

Cross-entropy determines the disparity among variables and the extent to which the variables are dissimilar to each other (Jabłońska, & Zajdel, 2020). As shown in the above table, the cross entropy error during training was equivalent to 74.333 (sample size at 127, 67.2% sample size), and the cross entropy error during testing was 31.400 (sample size at 62, 32.8% sample size). The percentage of inaccurate predictions in the training set was 21.3%, whereas it was 21.0% in the testing set. If the percentage of inaccurate predictions remains consistent between training and testing, the model is considered to be accurate. According to recent studies, there is hardly any difference between training and testing.

Table 5

Predictive Importance of Independent Factors

|

Sr# |

Variables |

Importance |

Normalized Importance |

|

1 |

Job status |

.065 |

13.7% |

|

2 |

Age |

.473 |

100% |

|

3 |

Education |

.348 |

73.5% |

|

4 |

Duration of job |

.114 |

24.1% |

Note. (N=191)

Inforation about the significance of predicting demographic characteristics for sexual harassment is provided by the neural network model. Age was found to be the most significant predictor of sexual harassment among police women, with a normalized importance of 100%. Education came in second with a normalized importance of 73.5%, followed by job tenure with a normalized importance of 24.1%, and job status with a normalized importance of 13.7%. All the four variables were contributing to the level of sexual harassment among police women. Figure 1 depicts the significance.

The ultimate result was the appearance of an understandable neural network model that clarified the significance of independent variables for sexual harassment of police women. The results were dominated by age, followed by education, length of employment, and work position, according to the importance chart.

Table 6

ANOVA of Sexual Harassment and Demographics (age, education, duration of job & job status) in Police Women

|

Sexual Harassment |

SS |

df |

MS |

F |

P |

|

Between Groups |

3.91 |

3 |

1.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.06 |

.002 |

|

Within Groups |

48.17 |

187 |

0.26 |

|

|

|

Total |

52.08 |

190 |

|

|

|

Note. (N=191); MS = mean square; SS = sum of square; p ˂. 05

Above table depicted a statistically significant difference among group means of demographics as determined by one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

Sexual persecution has risen to the forefront in the preceding two years as a problem that deserves larger devotion both in reports of public policy restructuring and educational investigation. Even though sexual provocation has been found to damagingly influence job gratification, work environment and mental health, there are very few studies about the particular means in which different demographics characteristics in executive positions influence the technique in which sexual pestering is professed. As females continue to rise to administrative positions, a faster inspection of both boss and subservient gender with respect to harassment penalties is necessary (Gilbert, 2005). All over the world every third woman is confronting sexual viciousness from a spouse, or from other individuals. A bitter fact is that at least 2.6 billion females are living in nations where sexual viciousness by the husband is still not deliberated as delinquency (UN Women Annual Report 2018–2019, n.d). Pakistan’s religious, financial, social and cultural paradigms are remarkably different from Western society (Syed, 2008). The Islamic faith and Pakistan's constitution both clearly indicate that women should be treated with respect and have equal access to human rights. In spite of this, Pakistan is still a place where male dominance is deeply ingrained in many spheres, making it difficult for women to secure their human rights (Akhtar & Métraux, 2013).

Literature on sexual harassment depicts that women employed in male dominant professions (e.g., police department) are more vulnerable to being sexually harassed than other females (Willness et al., 2007). Houle et al. (2011) identified that sexual harassment is a stressor at the workplace. Sexual harassment is more prevalent among women than among men. Further, issues related to sexual harassment have strong negative relationship to the overall organizational functioning and psychological wellbeing of employees.

The goal of this study was to determine the significance of various demographics as determinants of sexual harassment, and it was identified that age, education, job status and duration of job play an important part in sexual harassment of police women. The outcomes of the current investigation were also supported by earlier studies.

Odu and Olusegun (2012) conducted a study on 1200 sexually harassed and sexually coerced females from different workplaces. Findings of demographic linkage revealed age range, and marital status have significant association with sexual coercion. Furthermore, a higher level of sexual harassment was identified among unmarried and young ladies compared to married and older women. The prevalence of sexual harassment was shown to be higher among women in lower-ranking jobs, whereas it is less likely to occur among all female employees in higher ranks. Similarly, Sheets (2007) found a strong association between age and sexual violence among working women. Findings indicated that unmarried and young women are at high risk to experience sexual harassment related problems rather than married and older women. Furthermore, employers with lower level of education and working at lower job positions seem at a greater risk of being harassed as compared to their counter parts (Odu & Olusegun, 2012).

Covington, (1998) investigated that most mistreated, misunderstood and undetected population are women who are in prison. These women have no physical or mental security. They are sexually victimized women. The mentioned study also identified that women working in police department are also sexually harassed. But sexual misconduct is high amongst women who are young, less educated and working at lower positions.

In Pakistan, little literature is available regarding sexual harassment, particularly about females working in police department. Sexual harassment-related difficulties are causing a hostile work environment and a variety of issues, including stress, sadness, anxiety, and aggressive behavior. This study is particularly important since it examines how demographic parameters including age, education, employment status, and length of employment affect sexual harassment of female employees. Further, the current study points to the need to provide adequate awareness about sexual harassment to young women employees with a low level of education and those who are working as junior staff so that, the workplace environment could be protected for females.

Limitations and Suggestions

The Gujrat and Gujranwala districts' target population is covered by the current study's findings. These findings, however, cannot be applied to other district jails that are located in various geographic regions because this phenomenon can be very different there. It was particularly challenging to gather data for the sexual harassment questionnaire because the study issue was so sensitive. Further, it was challenging to obtain approval from jail administrations to conduct this type of study on female employees, which may have hampered the respondents' ability to provide accurate information. To improve the ability of the research findings to be generalized, it is suggested that a study on sexual harassment be conducted on a sizable and varied type of sample.

Implications

The current study, despite its shortcomings, offers adequate evidence to justify the implications of additional research on sexual harassment. Also, it offers some support for rethinking the methods typically employed in the police department to prevent sexual harassment of female employees. Because of the male dominance within the police department, sexual harassment-related concerns are not openly acknowledged. As a result, the findings of this study can be useful for policymakers and the management of the police department to gain knowledge and address this issue. The results of this study may also be useful in helping the higher authorities implement some preventative measures to raise awareness among the population. People could address concerns and insecurities related to sexual harassment with the help of these programs.

References

AASHA. (2002). Situational analysis of sexual harassment, Annual Report. Islamabad: AASHA.

Akhtar, N., & Métraux, A. (2013). Pakistan is a dangerous and insecure place for women. International Journal of World Peace, 30(2), 35–70.

Beseler, C.L., & Stallones, L. (2020). Using a Neural Network Analysis to Assess Stressors in the Farming Community. Safety, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety6020021

Burke, R.J., & Mikkelsen, A. (2004). Gender issues in policing: Do they matter? Women in Management Review, 20(2), 133-143. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420510584463

Burn, S. (2019). The psychology of sexual harassment. Teaching of Psychology, 46(1), 96-103. https://doi.org/: 10.1177/0098628318816183

Covington, S. S. (1998). Women in prison: Approaches in the treatment of our most invisible population. Women and Therapy Journal, 21(1), 141-155. https://doi.org/:10.4324/9781315783956-10

DeHaas, S., Timmerman, G., & Hoing, M. (2009). Sexual harassment and health among male and female police officers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(4), 390-401. https://doi.org/: 10.1037/a0017046

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(4), 578–589.

Fitzgerald, L., Magley, V. J., Drasgow, F., & Waldo, C. R. (1999). Measuring sexual harassment in the military: the sexual experiences questionnaire (SeQ-DoD). Military Psychology, 11(3), 243-263. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1103_3

Gilbert, J. A. (2005). Sexual Harassment and Demographic Diversity: Implications for Organizational Punishment. Public Personnel Management, 34(2), 161174. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600503400203

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. H. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction. New York: Springer.

House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. (2018). Sexual harassment of women and girls in public places. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmwomeq/701/701.pdf

Jabłońska, M. R., & Zajdel, R. (2020). Artificial neural networks for predicting social comparison effects among female Instagram users. PloS one, 15(2), e0229354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229354

Judicibus, M., & McCabe, M. P. (2001. Blaming the Target of Sexual Harassment: Impact of Gender Role, Sexist Attitudes, and Work Role. Sex Roles, 44(7), 401-417.

Kalof, L., Eby, K. K., Matheson, J. L., & Kroska, R. J. (2001). The Influence of Race and Gender on Student Self-Reports of Sexual Harassment by College Professors. Gender and Society, 15(2), 282–302. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3081848

Kamal, A. and N. Tariq. (1997). Sexual Harassment Experience Questionnaire for workplaces of Pakistan: Development and Validation. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 12, 1-20.

Konik, J., & Cortina, L. M. (2008). Policing gender at work: Intersections of harassment based on sex and sexuality. Social Justice Research, 21, 313–337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0074-z

Lavrakas, P. J. (2012). Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. Retrieved from http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/encyclopedia-of-survey-researchmethods/n120.xml

Lonsway, K. A., Paynich, R., & Hall, J. N. (2013). Sexual harassment in law enforcement: incidence, impact, and perception. Police Quarterly, 16(2), 177-210. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1098611113475630

McCann, J. (2005). Sexual harassment and public opinion. Springer, 36(11), 110-121.

Müller, U. P., Schröttle, M., Glammeier, S., Oppenheimer, C., Schulz, B. & Munster, A. (2006). Health, Well - Being and Personal Safety of Women in Germany: A representative study of violence against women in Germany. Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens: Women and Youth – BMFSFJ, 11018 Berlin.

Nieminen, T., Martelin, T., Koskinen, S., Simpura, J., Alanen, E., Härkänen, T., & Aromaa, A. (2008). Measurement and socio-demographic variation of social capital in a large population-based survey. Social Indicators Research, 85, 405-423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9102-x.

Numhauser-Henning, A., & Laulom, S. (2012). Harassment related to sex and sexual harassment law in 33 European countries: Discrimination versus dignity. EUR-OP.

Odu, B.K., & Olusegun, G.F. (2012). Determinant of Sexual Coercion among University Female Students in South-West Nigeria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 3, 915-920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0074

Ohse, D.M., Stockdale, M.S. (2008). Age Comparisons in Workplace Sexual Harassment Perceptions. Sex Roles 59, 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9438-y

Paludi, M. A. (Ed.). (1996). Sexual harassment on college campuses: Abusing the Ivory Power. State University of New York Press.

Pina, A., Gannon, T. A., & Saunders, B. (2009). An overview of the literature on sexual harassment: Perpetrator, theory, and treatment issues. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(2), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.002

Rabe-Hemp, C. (2007). Survival in an “all boys club”: Policewomen and their fight for acceptance. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 31(2), 251-270. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810878712

Sadruddin, M. M. (2013). Sexual Harassment at Workplace in Pakistan-Issues and Remedies about the Global Issue at Managerial Sector. Journal of Managerial Sciences, 7, 113-125.

Sheets, B., (2007). Women in the Criminal Justice System. Research and Advocacy for Reform, Washington, DC.

Schat, A., Frone, M., &Kelloway, E. (2006). Prevalence of work place aggression in the U.S. workforce. In Kelloway, E., Barling, J., & Burrell, J. (Ed.), Handbook of Workplace Violence (pp. 47-89). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Somvadee, C., & Morash, M. (2008). Dynamics of sexual harassment for policewomen working

alongside men. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 31(3), 485-498. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810895821

Syed, J. (2008). A context-specific perspective of equal employment opportunity in Islamic societies. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(1), 135–151.

Thompson, B. M., Kirk, A., & Brown, D. (2006). Sources of stress in policewomen: a three-factor model. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(3), 309-328. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.309

UN Women annual report 2018–2019. (n.d.). UN Women | Annual Report2015–2016. https://annualreport.unwomen.org/en/2019

Willness, C., Steel, P., & Lee, K. (2007). A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 127-162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00067.x

World Health Organization. (2022). Guidelines for medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence. 2003. WHO: Geneva.

Zandonda, P. N. N. (2011). A Study on Sexual Harassment of Women in Workplaces: A Case study of selected Public and Private Organizations in Ndola, Zambia (Doctoral dissertation