Asad Ahmad Rao*

Riphah Institute of Clinical & Professional Psychology, Lahore

Riphah Institute of Clinical & Professional Psychology, Lahore

The current study aims to investigate the relationship amongst violence against infertility, self- esteem, and psychological distress in women having infertility, and to ascertain the mediation effect of self-esteem between Violence against infertility and Psychological Distress. A purposive sampling strategy was used to collect a sample of 110 women having primary and secondary infertility. Infertile Women’s Exposure to Violence Determination Scale (Onat, 2014) was used to access Violence Against infertility, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, (Rosenberg, 1965) was used to measure the level of self-esteem and Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002) used to access psychological distress. The correlation was found through Product Moment Correlation Analysis and mediation was run using PROCESS (Hayes, 2013). The finding of the study suggested that violence against infertility was positively correlated with psychological distress and negatively correlated with Self-Esteem. A significant negative relationship was also found between psychological distress and self-esteem. self-esteem has a significant mediating effect on the relationship between violence against infertility and psychological distress. This study can help health practitioners and psychologists to work on mental health of women having infertility to decrease the impact of violence and psychological distress.

Keywords: infertility, primary infertility, secondary infertility, psychological distress

Infertility is defined as a disease of the reproductive system which includes an inability to achieve pregnancy in one year or more of the sexually active and non-contraceptive period in couples (Hochschild et al., 2009). In marital, personal, and social life, facing infertility has a very high impact as a distressful event for couples, and stress related to childlessness leads to remarkable emotional instability and couples with infertility become more anxious about childbirth that also leads to an increased risk of depression and social isolation (Deka & Sarma, 2010), and it also has a wide range of negative Psycho-Social consequences in different societies infer with a different interpretation of social, cultural, and religious demands of a child (Ericksen & Brunette, 1996). Women who mostly appear to carry the main burden are blamed for childlessness (Dyer et al., 2004), and punished for their infertility in the form of psychological and emotional harm with exclusion from the community, physical, and sexual abuse, and threats to divorce (Gerrits, 2002). Women with infertility experience more domestic violence than women having children (Okonofua, 2003), and psychological distress and other psychosocial factors related to infertility, have a significant impact on the treatment for infertility (Wright et al., 1989).

Violence is a broader term that is defined as force or power that can be threatening or actual, used intentionally against oneself or community, which can be the cause of injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development, or deprivation (World Health Organization [WHO], 2002). Riessman and Kohler (2000) showed in their study that women between the ages of 34 to 36 face the most stigma related to childlessness and marital conflicts. According to Ameh et al., (2007), women having infertility, experience psychological torture, verbal abuse, deprivation, social isolation, restrictions on financial recourses, and health care facilities, and this domestic violence results in physical abuse and divorce.

Psychological distress is an enclosed concept of a merged set of different attributes of mental strain, stress, anxiety, depression, and psychological suffering in collective manners (Ridner, 2004; Goldberg, 2012). Domar et al. (1992) found significantly higher depression and doubles the prevalence of depression in infertile women. Greil (1997) did a critical review of literature to find out the relationship between Psychological Distress and infertility, and found that over time psychological distress increases due to infertility, and the meta-analysis shows that psychological distress is greatly caused by infertility. Cwikel et al., (2004) reviewed many major studies to rule out psychological circular interaction with infertility and they found that psychological factors such as Stress, Depression, and Anxiety can play a major role in achieving normal pregnancy due to biological changes in these psychological states like changing in heart rate and cortisol level in the body.

Psychological violence has greater prevalence than physical Violence and has long-term consequences like trauma-related psychopathologies and a constant state of anxiety, fear, and depression. Psychological violence is the most common form of violence against infertile women (33.8%), followed by physical Violence (14%) (Behboodi et al., 201). According to Ardabily et al. (2010), despite differences in age, education level, maturity of husband, employment status of couples, and other demographic characteristics, domestic violence rate is the same in the case of infertility.

Self-esteem is a motivating and energizing power and it exhibits an optimum amount of self-achievement and enhances the sense of pleasure and pride in self and in all context, it enhances self-satisfaction in anyone (Branden, 1992). Negative attitudes towards self-esteem increase mental health vulnerability (Andrews & Brown, 1993). Lower self-esteem exhibits every aversive emotional state in people and it is also negatively correlated with state anxiety (Battle et al., 1988; Rawson, 1992). In the case of infertility sense of loss, trauma, anger, guilt, shock, feeling of shame and domestic violence are highly associated with lower self-esteem in the woman and build a sense of incompetency, and helplessness, and has a remarkable effect on their personal and social life. Women having infertility with low self-esteem are mostly concerned about their womanhood and are more effected with psychological distress related to their infertility problem (Abbey et al., 1992; Corning, 2002).

Unstable marital adjustment and low social support are indicators of psychological distress in infertile women (Qadir et al., 2015), and attachment style and social support play a crucial role for the individual during the time of stress and especially in the time of infertility (Amir et al., 1999). Easy access for women to social services and public health support, influences their physical and mental health, and it is necessary to reduce psychological distress among women (Gust et al., 2017)

The humanistic theory of need proposed by Maslow (1943) conceptualized self- determination as the need of self-esteem in the hierarchy of need, and explains it as a motivational force that determines an individual’s self-actualization. According to the humanistic theory, one must achieve physiological needs, security needs and belongingness needs to achieve self-esteem. Deci and Ryan (1995) explained three intrinsic needs which motivate individuals to achieve high self-esteem including relatedness, competency, and autonomy. Unstable and fluctuated competency, and autonomy cause low self-esteem, mood variations, and different physical symptom.

Women with infertility crises are more likely to have a significantly higher level of anxiety, depression, and aggression (Sultan & Tahir, 2011) and low self-esteem (Cox et al., 2006) as major consequences of violence against women in the form of abuse and battering (Haj- Yahia, 2000).

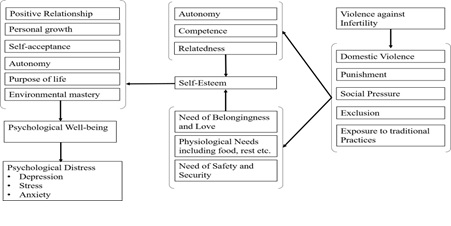

Onat (2004) divided violence against infertility into five domains: domestic violence, social pressure, punishment, exclusion, and exposure to traditional practices (Onat, 2004). In social and cultural aspects, women with infertility mostly experience domestic violence (Ameh et al., 2007), and go through extreme social pressure (Collins et al., 1992), as well as for childlessness (Berg, 1991), excluded from social and family rituals and exposed to punished different traditional and religious practices for fertility purposes which increase the tendency of suffering from depression, anxiety and physically affect their fertility outcome (Ardabily et al., 2011; Williams & Frieze, 2005). All these reported consequences of infertility affect their psychological well-being. Psychological well-being is a conceptualized term used not only to mean feeling good, but achieve living standards virtuously. Six factors defined by Ryff and D. (1989) are necessary to maintain psychological Well-being: positive relationships, personal growth, self-acceptance, autonomy, the purpose of life, and environmental mastery. The absence of any factor in the individual is not considered psychological wellbeing. Psycho-social consequences of infertility lead to psychological variability in individuals. Circumstances of infertility directly affect autonomy and relationships, and due to the traumatic effect of infertility most individuals lose their purpose of life and personal growth. Women with unstable psychological well-being experience a severe level of psychological distress due to their infertility. On the other hand, low self-esteem also affects their psychological well-being which increases the chance of psychological distress (Paradise et al., 2002). The model shown in Figure 1, conceptualizes the determinants of self-esteem and shows theoretical pathways of how violence against infertility predicts psychological distress, and how self-esteem plays a role as a mediator in the relationship of violence against infertility and psychological distress in women with infertility.

theoretical framework of Self-Esteem in relation with Violence against infertility and Psychological Distress

Violence in society amongst women having infertility has social, cultural, religious, and personal contexts. In Pakistan associated factors of depressive and anxiety disorders for 25.5% of women is marital conflicts, for 13% it is conflicts with in-laws, for 10% financial dependency, for 14% lack of jobs and for 9% it is stress of responsibilities (Mirza & Jenkins, 2004). The prevalence of infertility in Pakistan is 22% including 4% of primary infertility and 18% secondary infertility (Hakim et al., 2001). In Pakistan 67.7% of women having infertility reported, that they were threatened and blamed for their infertility by in-laws (51%) and husbands (38%). Nearly 21% of women were threatened with divorce, 26% were threatened to be sent back to their homes, and 38% were threatened by their husbands that they would remarry (Sami et al., 2006). Not only in Pakistan, but also in every region of the world women are expected to carry the whole burden of responsibilities including nourishment of family, and many personal and social factors associated with the distress in women’s lives and the most frequent and influenced factors included recurrent miscarriage, period of trying fertility without live birth, importance of motherhood, and long term treatment for infertility, are greatly associated with social and culture base distress (Shreffler et al., 2011). There is a large gap in identifying theoretical cognitive and psychological patterns related to infertility which can support reduction of the psychological distress in women having infertility. Current study is determined to fill this gap in order to reduce violence against infertility and associated mental health effects due to violence.

The correlational research design was proposed in nature to investigate the correlation between violence against infertility, self-esteem, and psychological distress.

The sample was chosen with specific characteristics based on prior researches. The purposive sampling strategy was used to collect data from 110 females with primary and secondary infertility. The sample was drawn from three infertility clinics located in the Punjab region of Pakistan. Infertile women were taken, based on the International Classification of Diseases (10th ed.) criteria of primary and secondary infertility. Participants between the age of puberty to 55 and with primary and secondary infertility were included. Participants with any form of uterine cancer, physical or mental disability and with a marital period of less than 1 year were excluded.

After approving the research topic by the Board of Advanced Studies and Research, the permission of the measuring psychometric instruments used in the present study was taken from the original authors and secondary authors who translated them. Infertile Women’s Exposure to Violence Determination Scale (IWEVDS) was translated using MAPI guidelines (UK) of tool translation. For data collection, permission was taken from three health care facilities including Civil Hospital Gujranwala, a gynecology clinic, and a polyclinic in Lahore, and the date and time for data collection were coordinated. Participants were approached at health facilities. Each participant was provided with detailed information about the research purpose and research process and a consent form were assigned to participants to make sure that they willingly participate in the research process. All participants were informed about all ethical considerations of the study. After that pilot study was conducted on five participants, from the

Gynecology clinic Lahore, Pakistan, for the estimation of the strength and validation of the questionnaires. They were briefed about the purpose of the study and asked about the difficulties they had faced during the process of data collection. The demographic questionnaire showed a little problem in some semi-structured questions which were modified later. After completing the assessment of data collection tools and demographics, it was assured that there was no error in data collection instruments and research was continued.

For the main study, the permissions were taken from the Heads of healthcare organizations to collect data from different healthcare facilities in two different cities. They were also informed about the main process, nature, and purpose of the research. In the main study, a total of 110 participants were included. All information about the research process was given to the participants through an information sheet and consent was taken from them through a consent form to assure willingness to participate in the research process. Participants were informed about their right of withdrawing from the research process if they feel uncomfortable. All questionnaires were administered by the researcher to the individual participant.

Permission to use psychometric instruments and translating the tools was taken from the original authors. For data collection, permission was taken from the head of the health care facilities. An information sheet was provided to the participant that included all information about the nature, purpose, procedure, duration of the research, their role as research participants, and contact of the appropriate person in the case of any difficulty. Consent was taken from the participants and they were assured that the information obtained from them will be kept confidential. Participants had assured that their rights of treatment in a related health care facility will not be affected by the research process, and they had the right to quit the research process anytime. The data was protected and entered into the computer program with codes and nobody other than the researcher and his supervisor had access to the data.

The data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 26 (SPSS- 26). In the first stage reliability analysis of psychological instruments used in research, was done. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the scales was obtained for reliability analysis which explained the internal consistency of measuring instruments shown in Table 1 below.

Psychometric Properties of Questionnaires (N=110)

Potential Actual

|

Distress Scale (K10)

(IWEVDS)

Note. k= Number of Items in the scale and sub-scale, M= Mean, SD= Standard Deviation, Min Score= Minimum Score, Max Score= Maximum Score, a= Reliability Co-efficient

The results shown in Table 1, indicate the Cronbach alpha reliability of the Infertile women’s exposure to the Violence determination scale (IWEVDS), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale is high.

The descriptive characteristics of demographic variables were calculated through mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage. Major descriptive characteristics of demographics are reported in Table 2.

Major Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Characteristics of Participants

|

Variables |

M (SD) |

ƒ (%) |

|

Age |

30.1 (5.27) |

|

|

Duration of marriage |

7.66 (4.97) |

|

|

Duration of Infertility |

5.76 (4.38) |

|

|

Numbers of Miscarriage |

.63(1.09) |

|

|

Total Home Income (PKR) |

37272.72 (19271.55) |

|

|

10000-19999 |

|

17 (15.5) |

|

20000-29999 |

|

51 (46.4) |

|

30000-39999 |

|

11 (10.0) |

|

40000-49999 |

|

4 (3.6) |

|

50000-59999 |

|

11 (10.0) |

|

60000-69999 |

|

5 (4.5) |

|

70000-79999 |

|

3 (2.7) |

|

80000-100000 |

|

4 (3.6) |

|

Above 100000 |

|

4 (3.6) |

|

Year of Education |

|

|

|

Not Educated |

|

14 (12.7) |

|

Primary |

|

15 (13.6) |

|

Middle |

|

12 (10.9) |

|

Matric |

|

21 (19.1) |

|

Intermediate |

|

19 (17.3) |

|

14 Year Education |

|

16 (14.5) |

|

16 Year Education |

|

11 (10.0) |

|

Post Graduate |

|

2 (1.8) |

|

Type of Infertility |

|

|

|

Primary |

|

73 (66.4) |

|

Secondary |

|

37 (33.6) |

Marital Satisfaction

Yes 77 (70.0)

No 33 (30.0)

Woman's Health perception

Unhealthy 6 (5.5)

Healthy 104 (94.5)

Note. M = Mean, SD = standard Deviation, f = Frequency

To ascertain the relationship amongst violence against Infertility, psychological distress, and demographic characteristics, Pearson Product Moment Correlation analysis was used. A series of hypotheses of correlation was tested through Pearson Product shown in Table 3 which

showed that there was a significant positive relationship found between violence against infertility and psychological distress, and a significant negative relationship found between violence against infertility and self-esteem. A significant negative relationship was also found between psychological distress and self-esteem. violence against infertility was also significantly positively correlated with the duration of infertility and negatively correlated with marital satisfaction. There was also a positive correlation found between the psychological distress and duration of infertility. While women’s level of education, home monthly income, and marital satisfaction was negatively correlated with psychological distress. self-esteem was significantly positively correlated with marital satisfaction and monthly income.

Correlation between Violence, its Sub-Scales, Self-esteem, Psychological Distress, and Demographic characteristics of participants

|

Variables |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

VAI |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SE |

-.26** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PD |

.52** |

-.31** |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

.11 |

-.08 |

.06 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edu |

-.19* |

-.08 |

-.30** |

.06 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FT |

-.02 |

.06 |

.55 |

-.96 |

-.04 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MI |

.19* |

.23* |

-.32** |

.06 |

.35** |

.10 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TI |

-.12 |

.12 |

.05 |

.14 |

-.12 |

.07 |

-.04 |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

DOM |

.12 |

-.02 |

.10 |

.64** |

-.22* |

-.04 |

-.08 |

.15 |

- |

|

|

|

|

HP |

-.17 |

.05 |

-.18 |

-.11 |

.30** |

.16 |

-.12 |

-.00 |

.06 |

- |

|

|

|

DOI |

.20* |

-.13 |

.22* |

.67** |

-.24* |

-.09 |

-.06 |

-.04 |

83** |

-.16 |

- |

|

|

MS |

-.56** |

.28** |

-.54** |

-.07 |

.19* |

.05 |

.17 |

-.03 |

-.11 |

-.16 |

-.18 |

- |

|

NM |

-.20 |

.11 |

.03 |

.02 |

-.05 |

.04 |

-.05 |

-.12 |

.06 |

.00 |

.01 |

-.16 |

Note. VAI = Violence against infertility, PD = Psychological distress, Edu = Education (1= Non Educated, 2= Primary, 3= Middle, 4= Matric, 5= Intermediate, 6= 14 year education, 7= 16 year education, 8= Postgraduate), FT = Family type (1 = Nuclear, 2 = Joint), MI = Monthly income, TI = Type of infertility (1 = Primary, 2 = Secondary), DOM = Duration of Marriage (in years), HP = Health Perception (1 = Unhealthy, 2 = healthy), DOI = Duration of infertility, MS = Marital satisfaction (1 = satisfied, 2 = Not Satisfied), NM = Number of miscarriages, * = P<.05, ** = P<.005, *** = P<.001

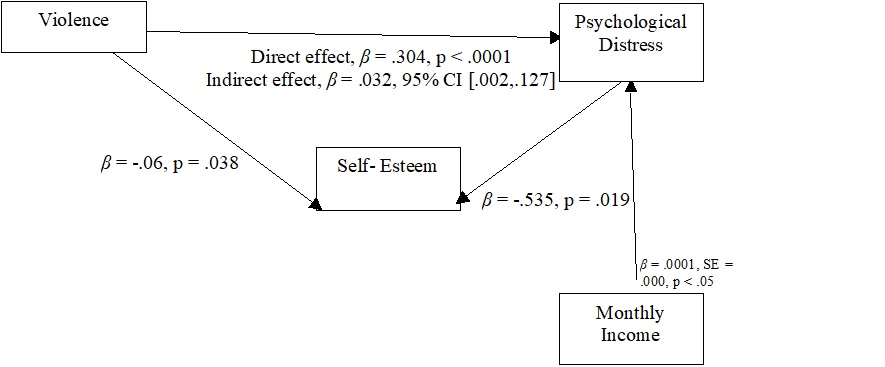

Prediction and mediation of variables were found through PROCESS developed by Hayes (2012). In the mediation model-independent, the variable Violence against Infertility was added as a predictor, self-esteem was added to the mediator and psychological distress was added to the outcome. The results are presented in Table 4 and Figure 3.

Model of Mediation with results

Table 4 shows that the predictor variable violence against infertility have significant direct effect on self-esteem, (B = -.07, SE = .03, p < .05) with 15% variance explained in self- esteem by violence, F (11, 98) = 1.60, p > .05. Mediator variable self-esteem was significantly negatively predicted psychological distress (B = -.54, SE = .23, p < .05) with 40% variance explained in psychological distress by violence F (12, 97) = 5.47, p < .001. Only Home Income has significantly predicted psychological distress as co-variate (B = .0001, SE = .000, p < .05).

Direct Pathways Between Violence Against Infertility (Predictor Variable), Self-Esteem (Mediator Variable), And Psychological Distress (Outcome Variable). (N= 110)

Self-Esteem Psychological Distress

|

|

β |

SE |

β |

SE |

|

Violence |

-.06* |

.02 |

.30*** |

.06 |

|

Self-Esteem |

|

|

-.53* |

.22 |

|

Age |

-.08 |

.08 |

-.08 |

.18 |

|

Duration of Marriage |

.10 |

.10 |

.30 |

.22 |

|

Monthly Income |

.00 |

.00 |

.00* |

.00 |

|

Family Type |

.48 |

.71 |

.57 |

1.59 |

|

Marital Satisfaction |

-.40 |

.33 |

1.44 |

.75 |

|

Health Perception |

.89 |

.61 |

.79 |

1.39 |

|

Number of miscarriages |

.30 |

.30 |

.64 |

.67 |

|

Type of Infertility |

.44 |

.73 |

2.55 |

1.63 |

|

Duration of Infertility |

-.19 |

.13 |

-.42 |

.29 |

R2 .15 .40***

Note. β =Co-efficient, SE=Standard Error, R2=Variance

Indirect Effects of Violence against Infertility (Predictor variable) on Psychological Distress (Outcome Variable) through Self-Esteem (Mediator Variable; N= 110)

|

|

Psychological Distress |

|

|

β |

SE |

95% Cl |

|

Violence .03 |

.03 |

LL UL .001 .13 |

Note. β= Co-efficient, SE= Standard error, CI= Confidence interval, LL= Lowe Limit, UL= Upper Limit

Table 5 shows that self-esteem has a significant mediating effect in the relationship between violence and psychological distress after controlling covariates.

The results showed that a greater range of violence against infertility is highly correlated with psychological distress as well as negatively correlated with self-esteem. Self-esteem was found to be a significant mediator in the relationship between violence and psychological distress.

This study explored the psycho-social aspects of infertility faced by women in different cultural and family environments. It aimed to explore violence against infertility with psychological distress and identify the effect of self-esteem as the mediator between violence and psychological distress. The present study indicated that women with infertility show greater victimization of violence against infertility will be more psychological distressed. It is following previous research which states that women with infertility do not only suffer from their feeling of incompetency, but also that face cultural, religious, and family base violence which directly affects their mental and physical health (Ellsberg et al., 2008), and the women with a history of violence face a high level of psychological distress as compared to women with no history of a violent relationship (Williams & Frieze, 2005; Vives-Cases et al., 2010; Ellsberg et al., 2008). Previous studies support the findings of the current study that violence against infertility predicts higher psychological distress in women having infertility.

The current study found a significant negative correlation between violence and self- esteem. A study concluded that abused women have a greater sense of control, depressive symptoms, and lower levels of self-esteem than compare women with no abuse history (Orava et al., 1996; Baumeiste et al., 1996). The present study also revealed that women with a history of violence showed an increased level of psychological distress and a low level of self-esteem.

Results of the current study showed that women with infertility had a greater tendency to be psychologically distressed, as well as with a higher level of psychological distress, and their self-esteem had tended to below. According to previous literature, a high level of psychological distress led to a lower level of self-esteem. Cox et al. (2006) and Wright et al. (1991) established a significant relationship between self-esteem and anxiety, depression, and psychological distress and revealed that self-esteem increased with the growth of pregnancy, and anxiety symptoms decreased as well. Previous studies share the same results as the current study has concluded. Women having infertility not only suffer from violence directly, but this violence contributes to lowering their self-esteem and it causes a higher level of psychological distress.

This study found self-esteem as a mediator in the relationship between violence and psychological distress, and there was also a significant direct correlation found between violence, self-esteem, and psychological distress. But through indirect pathways lower levels of self- esteem more effectively increase psychological distress as compared to violence. Previous work

indicates that self-esteem influences the relationship of violence and psychological distress as a moderator. Corning (2002) and Orava et al. (1996) found in their study that there is significant inverse direct effect of self-esteem on psychological distress and self-esteem with moderator effect on the relationship of psychological distress, violence, and perceived discrimination as the present study has indicated, the inverse direct effect of self-esteem on psychological distress. These results support the findings of the current study.

Most of the women having infertility who participated in this study and were found with psychological distress have had a primary type of infertility (66.6%) and the mean age range of participants was 31 years. A study conducted by Imran et al. (2017) on women with primary and secondary infertility found that 55% of women with depression had a primary type of infertility and most of them were between the age of 26 to 35. Berg and Wilson (1991) reported that those couples under treatment for infertility was associated with a higher level of psychological distress, lower marital satisfaction in the first and third year of treatment. Similarly, the current study found that most of the women had a primary type of infertility and trying for childbirth for more than 5 years and a period of infertility was found to be the leading factor which caused an increase in the level of psychological distress. It was also found that most of the participants were not satisfied with their marital life. Jeyaseelan et al. (2007) and Mao and Wood, (1984) explored the risk factors and protective factors for lifetime experience of violence in women and the study showed a strong association with domestic violence with lower socioeconomic status due to stress. The study also found education as a protective factor against spousal violence, and lower education status was reported as the cause of lower communication between couples which leads to domestic violence. But in the case of infertility where infertility treatment is required, lower socioeconomic status is hardly stressful for women especially when they cannot afford their treatment despite experiencing violence (Mirza & Jenkins, 2004). The current study found that most of the women with infertility had lower socioeconomic status, and would not financially afford the treatment of Infertility and there was a significant positive correlation found between socioeconomic status and self-esteem.

The present study aimed to explore the relationship between violence against infertility, self-esteem and psychological distress and to ascertain the role of self-esteem as the mediator between the relationship of violence against infertility and psychological distress in women having infertility. Research findings showed that violence against women with infertility results in more psychological distress and lessens self-esteem. Results also showed that self-esteem is significant mediating effect in the relationship of violence against infertility and psychological distress. These results indicated that women with infertility who face violence against their infertility are not only affected by the violence which leads to psychological distress, but their self-esteem plays a major role in the development of psychological distress. Violence against women infertility has a significant impact on their self-esteem. This study concluded that the theoretical framework of pathways defines how violence against infertility causes psychological distress through indirect pathway of self-esteem. This framework can help in the development of psychological intervention for women with infertility to reduce the violence against infertility and its impact in the form of psychological distress. Furthermore, studies are required to fill the gap in research related to psychological interventions for women having infertility and reduce the consequences of violence against women with infertility.

Women with infertility need to be considered as a highly vulnerable group of society, thus this study calls for many important future implications including:

Abbey, A., Andrews, F. M., & Halman, L. J. (1992). Infertility and subjective well-being: The mediating roles of self-esteem, internal control, and interpersonal conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 408-417. https://doi.org/10.2307/353072

Ameh, N., Kene, T. S., Onuh, S. O., Okohue, J. E., Umeora, O. U., & Anozie, O. B. (2007). Burden of domestic violence amongst infertile women attending infertility clinics in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 16 (4), 375-377.

https://doi.org/10.4314/NJM.V16I4.37342

Amir, M., Horesh, N. & Lin-Stein, T. Infertility and Adjustment in Women: The Effects of Attachment Style and Social Support. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 6, 463–479 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026280017092

Andrews, B., & Brown, G. W. (1993). Self-esteem and vulnerability to depression: The concurrent validity of interview and questionnaire measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(4), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.4.565

Ardabily, H. E., Moghadam, Z. B., Salsali, M., Ramezanzadeh, F., & Nedjat, S. (2011). Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian

setting. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 112 (1), 15-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.030

Battle, J., Jarratt, L., Smit, S., & Precht, D. (1988). Relations among Self-Esteem, Depression and Anxiety of Children. Psychological Reports, 62(3), 999–

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological review, 103(1), 5-33. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.103.1.5

Behboodi Moghadam, Z. (2012). To determine the prevalence and risk factors of domestic violence against women with female-factor infertility in an Iranian setting. International Journal of Fertility and Sterility, 6(1), 144.

https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=277844

Berg, B.J., Wilson, J.F. (1991). Psychological functioning across stages of treatment for infertility. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14, 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844765

Branden, N. (1992). Power of Self Esteem. Barnes & Noble Books.

van Balen, F., & Trimbos-Kemper, T. C. (1993). Long-term infertile couples: A study of their well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 14, 53-60.

https://europepmc.org/article/med/8142990

Collins, A., Freeman, E. W., Boxer, A. S., & Tureck, R. (1992). Perceptions of infertility and treatment stress in females as compared with males entering in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertility and Sterility, 57(2), 350-356. https://doi.org/ 10.1016 /S0015-

0282(16)54844-4

Corning, A. F. (2002). Self-esteem as a moderator between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49 (1), 117– 126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.1.117

Cox, S. J., Glazebrook, C., Sheard, C., Ndukwe, G., & Oates, M. (2006). Maternal self-esteem after successful treatment for infertility. Fertility and sterility, 85 (1), 84-89.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1287

Cwikel, J., Gidron, Y., & Sheiner, E. (2004). Psychological interactions with infertility among women. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 117(2), 126-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb. 2004.05.004

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18 (1), 105-115. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/h0030644

Deka, P. K., & Sarma, S. (2010). Psychological aspects of infertility. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 3(3), 1757-8515. https://www.bjmp.org/files/2010-3-3/bjmp-2010-3-3- a336.pdf

Domar, A. D., Broome, A., Zuttermeister, P. C., Seibel, M., & Friedman, R. (1992). The prevalence and predictability of depression in infertile women. Fertility and sterility, 58(6), 1158-1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)55562-9

Dyer, S. J., Abrahams, N., Hoffman, M., & van der Spuy, Z. M. (2002). Men leave me as I cannot have children': Women's experiences with involuntary childlessness. Human Reproduction, 17(6), 1663-1668. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.6.1663

Dyer, S. J., Abrahams, N., Mokoena, N. E., & van der Spuy, Z. M. (2004). ‘You are a man because you have children’: Experiences, reproductive health knowledge and treatment-seeking behavior among men suffering from couple infertility in South Africa. Human Reproduction, 19(4), 960-967. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh195

Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A., Heise, L., Watts, C. H., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2008). Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. The Lancet, 371(9619), 1165-1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X

Ericksen, K., & Brunette, T. (1996). Patterns and predictors of infertility among African women: a cross-national survey of twenty-seven nations. Social Science & Medicine, 42 (2), 209- 220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00087-9

Gerrits, T. (1997). Social and cultural aspects of infertility in Mozambique. Patient Education and Counseling, 31(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(97)01018-5

Goldberg, D. (2000). Distinguishing mental illness in primary care: Mental illness or mental distress? British Medical Journal, 321 (7247), 1420-1421.

https://doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.320.7247.1420

Greil, A. L. (1997). Infertility and psychological distress: A critical review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 45(11), 1679-1704. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0277- 9536(97)00102-0

Gust, D. A., Gvetadze, R. J., Furtado, M., Makanga, M., Akelo, V., Ondenge, K., Nyagol, B., & McLellan-Lemal, E. (2017). Factors associated with psychological distress among young women in Kisumu, Kenya. International Journal of Women's Health, 9, 255- 264. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S125133

Haj-Yahia, M. M. (2000). Implications of wife abuse and battering for self-esteem, depression, and anxiety as revealed by the second Palestinian national survey on violence against women. Journal of Family Issues, 21(4), 435-463.

https://doi.org/10.1177/019251300021004002

Hakim, A., Sultan, M., Fakhar Din. (2001). Pakistan reproductive health and family planning survey preliminary report. National Institute of Population Studies, Islamabad, Pakistan. https://www.nips.org.pk/

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 219–266). IAP Information Age Publishing. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-01991-006

Hochschild, F. Z., Adamson, G. D., Mouzon, J. D., Ishihara, O., Mansour R., Nygren, K., … Poel, V. D. (2009). The international committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technology [ICMART] and the world health organization [WHO] revised glossary on assisted reproductive terminology [ART]. Human Reproduction, 24(11), 2683–2687. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep343

Imran, S. S., & Ramzan, M. (2017). Depression among primary and secondary infertile women: Do education and employment play any role? Annals of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, 13(1), 39-42. https://apims.net/apims_old/Volumes/Vol13-1

Jeyaseelan, L., Kumar, S., Neelakantan, N., Peedicayil, A., Pillai, R., & Duvvury, N. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(5), 657-670. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0021932007001836

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., T. Normand, E. Walters & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959-976. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0033291702006074

Mao, K., & Wood, C. (1984). Barriers to treatment of infertility by in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. The Medical Journal of Australia, 140(9), 532-533. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1984.tb108227.x

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370– 396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Mirza, I., & Jenkins, R. (2004). Risk factors, prevalence, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan: Systematic review. The British Medical Journal, 328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7443.794

Okonofua, F. (2003). New reproductive technologies and infertility treatment in Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 7(1), 7-11. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3583339

Onat, G. (2014). Development of a scale for determining violence against infertile women: A scale development study. Reproductive Health, 11(18). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742- 4755-11-18

Orava, T. A., McLeod, P. J., & Sharpe, D. (1996). Perceptions of control, depressive symptomatology, and self-esteem of women in transition from abusive

relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 11(2), 167-186. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02336668

Paradise, A. W., & Kernis, M. H. (2002). Self-esteem and psychological well-being: Implications of fragile self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21(4), 345-361. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.21.4.345.22598

Qadir, F., Khalid, A., & Medhin, G. (2015). Social support, marital adjustment, and psychological distress among women with primary infertility in Pakistan. Women & Health, 55(4), 432-446. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2015.1022687

Rawson, H. E. (1992). The interrelationship of measures of manifest anxiety, self-esteem, locus of control, and depression in children with behavior problems. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 10(4), 319-329. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428

299201000402

Ridner, S. H. (2004). Psychological distress: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(5), 536-545. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x

Riessman, C. K. (2000). Stigma and everyday resistance practices: Childless women in South India. Gender & Society, 14(1), 111-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891 24300014001007

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069– 1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sami, N., & Ali, T. S. (2006). Psycho-social consequences of secondary infertility in Karachi. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 56(1), 19-22. https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_chs_chs/276

Shreffler, K. M., Greil, A. L., & McQuillan, J. (2017). Responding to infertility: Lessons from a growing body of research and suggested guidelines for practice. Family Relations, 66(4), 644-658. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12281

Sultan, S., & Tahir, A. (2011). Psychological consequences of infertility. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 8, 229-247. https://pseve.org/wp- content/uploads/2018/03/Volume08_Issue2_Soultan.pdf

Vives-Cases, C., Ruiz-Cantero, M. T., Escribà-Agüir, V., & Miralles, J. J. (2010). The effect of intimate partner violence and other forms of violence against women on health. Journal of Public Health, 33(1), 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1093 /pubmed/fdq101

Williams, S. L., & Frieze, I. H. (2005). Patterns of violent relationships, psychological distress, and marital satisfaction in a national sample of men and women. Sex Roles, 52(11-12), 771-784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-4198-4

Wright, J., Allard, M., Lecours, A., & Sabourin, S., (1989). Psychosocial distress and infertility: A review of controlled research. International Journal of Fertility, 34(2), 126-142. https://europepmc.org/article/med/2565316

Wright, J., Bissonnette, F., Duchesne, C., Benoit, J., Sabourin, S., & Girard, Y. (1991) Psychosocial distress and infertility: Men and women respond differently. Fertility and Sterility, 55(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54067-9