Loneliness and Aggression in Adolescents Living in Institutionalized Care

Ayesha Abdul Khaliq

Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning

Iram Fatima

University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Maryam Iftikhar

University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Qurat ul Ain Alam

University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

A cross-sectional study was conducted to find out the relationship between loneliness and aggression among adolescents living in institutionalized care. Data were collected from 120 boys and 120 girls with an age range of 11 to 18 years (M = 14.61, SD = 1.92). It was hypothesized that loneliness would predict aggression differently in girls and boys. The assessment was made with Buss and Perry aggression questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) and UCLA loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1980). Results from hierarchical regression analyses revealed that adolescents perceiving a higher level of loneliness expressed more physical aggression similarly in both girls and boys. However, Loneliness positively predicted verbal aggression and hostility in girls but not in boys. Further, generally, girls expressed more anger than boys

Keywords: loneliness, aggression, adolescents, institutionalized care

In the last decade, the prevalence of loneliness in adolescents rose from 4.4% to 7.1% in Denmark in recent years (Madsen et al., 2019). The increase in the ratio is alarming and thus becoming a public health problem. Loneliness is characterized by unpleasant feelings that arise when an individual perceives a discrepancy between their desired and existing social relationships (Mushtaq et al., 2014). It is therefore a subjective experience, and distinct from the objective condition of aloneness and cannot be simply predicted by objective indicators (Laursen & Hartl, 2013). Agreeing to its subjectivity, however, different components of loneliness were studied by different theoretical frameworks. Emphasizing the emotional component of loneliness, the social needs method is grounded in psychodynamic theory (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989) while focusing on the discrepancy between actual- and desired social relationships, the cognitive approach stresses on perception and evaluation of social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982).

Loneliness, particularly in adolescence, has consistently been associated with many neagative physical (Stickley et al., 2014), mental, behavioural, and emotional health outcomes (Vanhalst et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). During adolescence, chronically high levels of loneliness are found to be associated social-skills deficits (Friedler et al., 2015), suicidality, hopelessness (Schinka et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2010) withdrawing from social interaction (Ayalon & Shiovitz, 2011) and depression (Qualter & Brown, 2010). Along with the above mentioned wide range of psychosocial and emotional problems, loneliness is found to be strongly associated with aggression (Friedler et al., 2015; Yavuzer et al., 2019). Aggression is typically called a behaviour that is intended to harm oneself and others (Baron & Richardson, 1994). The most common and dangerous form of aggression is direct physical aggression that includes hits, slaps, kicks, and stabs, whereas other ways of aggression can be equally harmful. A relatively recent review also confirms physical abuse as more harmful along with the explanation that victim of psychological aggression perceives it more dangerous and long-lasting effects and described some other obvious forms of aggression such as verbal aggression, relational aggression, passive aggression, indirect aggression, emotional aggression, and psychological aggression (William et al., 2012).

M T'ng et al. (2020) found loneliness positively predicted all four components of aggression. Similarly, Dey (2018) reported a significant positive relationship between loneliness and aggression in adolescents with a high ratio of aggression in boys as compared to girls. Carrizales (2007) found a strong positive relationship between aggression, loneliness, and suicidality in the incarcerated juvenile population. Researches provides the evidence that anger and hostility leads to the aggression in males and anger is found to be cued to the verbal as well as physical aggression in them (Fives et al., 2011).

All these psychosocial issues get worse and the level of loneliness increases when it comes to living in institutionalized care settings such as orphanages (Kutlu, 2016). In a study, it was found that the quality of life of children living with families was far better than those who were living in institutionalized care (Nakatomi et al., 2018). Adolescents living in institutionalized care may face repeated abuse, neglect, and fears, which eventually contribute towards the assumption of having a disproportionately high prevalence of mental health disorders (Havlicek et al., 2013; Pecora et al., 2009). Research studies have indicated that children in institutionalized care homes suffer from moderate to severe mental health issues (DosReis et al., 2001; Simms et al., 2000).

Children living in special/ institutionalized care settings show more self-esteem and externalizing behavioral problems (Nsabimana et al., 2019). Their existing difficulties make them more vulnerable to many psychological issues, which may manifest in later years (Atwine et al., 2012). These effects of institutionalization appear to be more detrimental and long‐lasting in boys as compared to girls (Bos et al., 2011; Zeanah et al., 2009).

Although several studies reveal the relationship of perceived loneliness and aggressive tendencies in general, there is a dearth of studies exploring the relationship of loneliness with aggressive behaviors among adolescents living in institutionalized care. Based on the knowledge that psychosocial problems of those not living in families are more than those living with families, the current research aimed to understand the role of perceived loneliness in the aggression of adolescents living in institutionalized care in Pakistan. The rationale of the study is to provide the basis to develop culturally tailored interventions for institutionalized residents and arranging background for the mental health policymakers. Therefore, the objective of the current study was as follows

Objectives of the Study

- To assess the relationship of loneliness with aggression in adolescent boys and girls living in institutionalized care.

- Loneliness will predict different aspects of aggression in boys and girls.

- Gender will moderate the relationship between loneliness and different aspects of aggression.

Method

Research Design

A Cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the relationship of loneliness with various dimensions of aggression in adolescents living in institutionalized care.

Sample

TData was collected from 240 adolescents living in two public sector institutions situated in Lahore, which provide long-term residence and care to children who have either one or both of their parent’s deceased or children of parents who are separated. One institution was exclusively for girls and the other was only for boys. The required age for admission in these institutions is 4 to 10 years. Children can stay there till the age of 18 years except for exceptional reasons. Data were collected from 120 boys and 120 girls aged between 12 to 18 years. Average age of girls in years (M = 14.91, SD = 2.01) was more than boys (M = 14.32, SD = 1.78), t (238) =2.37, p = .02. The minimum duration of any adolescent’s stay in the institution was 3 years at the time of data collection. Study dind’t specifically focused on ethnicity as the aim of the study was only to focus on the psychological issues facing by these children living in an institutionalized settings.

Measures

Demographic Information Questionnaire

A demographic information questionnaire was used to get information about age, gender, and education.

Buss and Perry Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992)It consists of 29 items including four subscales that measure four aspects of trait aggressiveness—anger (7 items), hostility (8 items), verbal aggression (5 items), and physical- aggression (9 items). Response categories are 1=Extremely uncharacteristic of me, 2= Somewhat uncharacteristic of me, 3= Neither characteristics nor uncharacteristic, 4= Somewhat characteristic of me, 5= Extremely characteristic of me. Two of the items have reverse scoring. Internal consistency of four subscales in Pakistani has been reported to be .80, .89, .72, and .57 respectively (Batool & Bond, 2015). In current research the reliability for anger, hostility, verbal aggression and physical aggression was .82, .84, .70 and .62 respectively.

UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980)It is a unidimensional scale consisting of 20 items with 10 positively stated and 10 negatively stated items. Participants rate each item on a scale from 1 (Never) to 4 (Often). Negatively stated items are reverse scored to obtain a score on loneliness. A high score represents a high level of perceived loneliness. Cronbach alpha of the scale in Pakistan has been reported to be .90 (Anjum, & Batool, 2016). Current study reports the Cronbach alps of .88 for UCLA.

Procedure

After the formal permission from the administration of the institutes, appointment was taken from meet the children. The children were met after school before lunch, and those willing to participate were asked to fill the questionnaire. They were settled down in their combined study room. One of the members from the organizers of the institution was present during the process of data collection. The data was collected in the form of groups. Participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study and were ensured of privacy regarding their identity. Informed consent was distributed among the participants and they were given the questionnaire to fill it up. Participants were given instructions to fill the questionnaire and explanation regarding the study. None of the students declined to complete the questionnaire. The participants took 20 to 30 minutes to complete the questionnaires.

Ethical ConsiderationFormal permission was taken from the Institute of Applied Psychology to conduct the study. Permission to use the scales was also taken from authors. Written consent was taken from managers of the institutions where adolescents were residing as their guardians. Written consent was also taken from students before data collection.

Results

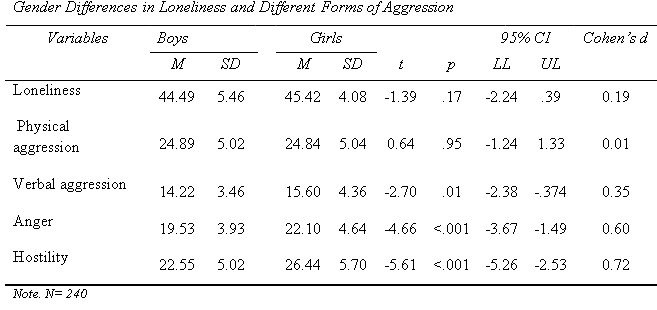

Independent sample t-test was used to make the comparison of girls and boys on aggression and loneliness. Results from the t-test reveal that there were no significant gender differences in loneliness and physical aggression while girls showed more verbal aggression, anger, and hostility as compared to boys. (See table 1).

Table 1

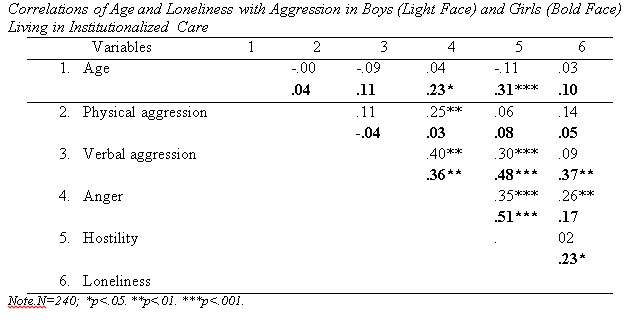

The results from Pearson Product moment correlation as depicted in table 2 reveal that in boys only anger was related to loneliness while in girls verbal aggression and hostility were related to loneliness. While physical aggression was correlated with anger in boys. Further, verbal aggression was related to anger and hostility in both boys and girls. The relationship of age with all variables was also assessed to check for any possible confounding. Age was found to be positively related to anger and hostility in girls.

Participants who were homeless showed significant differences between the mean scores, F (27, 762.89) = 1.73, p = .012; Wilks’ Lambda = .84; partial eta squared = .05. On the other hand, participants who were living in tents also showed significant differences on PTSD and PTG as evident by F (27, 762.89) = 1.66, p = .019; Wilks’ Lambda = .846; partial eta squared = .05. Similarly, participants who experienced loss of crops also performed differently on the mean scores of PTSD and PTG F (27, 762.89) = 2.29, p < .001; Wilks’ Lambda = .796; partial eta squared = .07.

Table 2

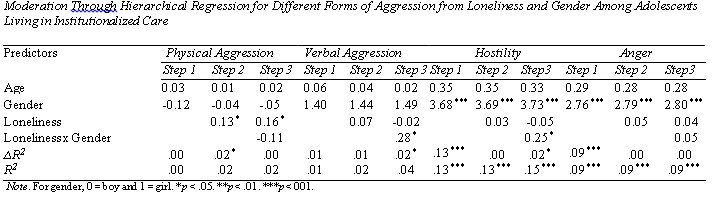

Series of hierarchical regression analyses were run to assess the predictive role of loneliness and its interaction with gender in four dimensions of aggression. Age was entered as a covariate in all analyses as it was found to be related to two aspects of aggression in girls. For all analyses, the first step is comprised of demographic variables, age, and gender. In the second step, loneliness was entered while in the third step product of gender and loneliness was entered. Assumption of no multicollinearity and independence of errors were assessed with values of tolerance and Durbin Watson respectively. Tolerance values varied from .97 to .99 and values of Durbin Watson ranged from 1.59 to 2.07. Thus, both assumptions were fulfilled. The main effects of gender and loneliness were interpreted from step two and interaction effects were interpreted from step 3. Unstandardized regression weights have been reported for all steps.

Table 3

Results in table 3 show that for physical aggression overall model explained a 2% variance. Only loneliness positively predicted physical aggression. Interaction of gender and loneliness also did not predict physical aggression, which indicates that loneliness predicted physical aggression in both girls and boys similarly.

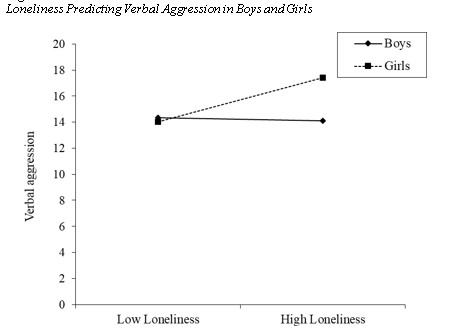

For verbal aggression, the overall model explained a 4 % variance. Only the interaction of gender and loneliness predicted verbal aggression. To explore the interaction effect further, a simple slope analysis was run (Dawson, 2014). Loneliness positively predicted verbal aggression in girls, B = .27, p = .02 but not in boys, B = -.02, p = .82. (See figure 1 for interaction plot for verbal aggression).

Figure 1

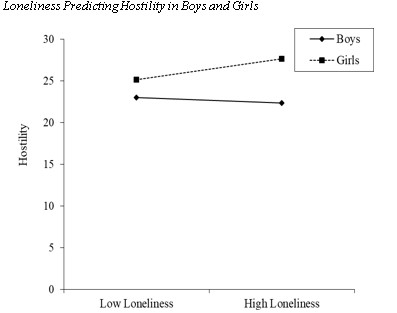

For hostility, the overall model explained a 15 % variance. The only gender predicted hostility with girls expressing more hostility as compared to boys. The interaction of gender and loneliness was also significant. Simple slope analysis (Dawson 2014) was conducted to further understand the differential role of loneliness in boys and girls regarding hostility. It was observed that loneliness positively predicted hostility in girls, B = .20, p = .04. However, loneliness did not predict hostility in boys, B = -.05, p = .43. Results are depicted in figure 2

Figure 2

For anger, the overall model explained a 9 % variance. Here again, only gender predicted hostility with girls expressing more anger as compared to boys. However, Interaction was not significant which shows that this difference was similar at different levels of loneliness.

Overall it was observed that adolescents perceiving a higher level of loneliness expressed more physical aggression irrespective of their gender. However, Loneliness positively predicted verbal aggression and hostility in girls but not in boys. Further, generally, girls expressed more anger than boys.

Discussion

Globally, millions of children live in institutionalized care to the age of adolescence. Unfortunately, findings of a recent systematic review revealed South Asia has the largest number of 1.13 million children living in institutionalized care (Desmond et al., 2020). Many studies in past, have investigated the different aspects of lives of these children and reported malnutrition and maltreatment, poor quality impersonal care, risk of physical and emotional abuse and showed they are easily exploited and might haven’t met their medical needs (Berens & Nelson, 2015; Csáky, 2009; Dozier et al., 2012; Jozefiak & Kayed, 2015; Lacey et al., 2020; UNICEF, 2009). The main purpose of this study was to investigate psychosocial problems particularly, loneliness and aggression among children living in institutionalized care in Pakistan. It aimed to find out the relationship between loneliness and aggression among these institutionalized adolescents

It was observed that loneliness predicted physical aggression in adolescents as expected. The finding are in line with the results drawn by Carrizales (2007), Dey (2018), and T'ng et al.,(2020). In an institutional care, many children and adolescents live together and they are not evaluated alone by others. But suggest that social support and psychological capital can reduce the feeling of loneliness among adolescents but there is a great a discrepancy related to perceived loneliness and peer-evaluated loneliness (Ren & Ji, 2019; (Lodder et al., 2016). An adolescent is the distinctive phase of hasty physiological and psychological growth. Due to the rapid changes in this time, adolescents often suffer from several psychological and emotional issues (Chung et al., 2019). Loneliness is one of these issues that adolescents face (Twenge et al., 2019). Adolescents living in institutionalized care and perceiving more loneliness due to lack of intimate relationships in the institutions might be more prone to physical aggression due to lack of parental guidance and monitoring which is available in traditional families.

Loneliness also predicted verbal aggression and hostility as expected but in girls only. Girls and boys react differently to their problems (Fischer et al., 2018). Girls, generally accept their feelings and express them verbally more than boys. Further, the expression of feelings is more acceptable for girls in a male-dominated society where boys are considered stronger than girls. This may be the reason that in the current study girls reacted to their loneliness with hostility and verbal aggression but boys were unable to express their feelings.

Another finding of the study was that generally, girls were angrier than boys. And loneliness did not predict anger. This is in contrast to studies conducted in the West and in the general population where the higher level of anger and all forms of aggression in boys has been observed (Bos et al., 2011; Chung et al., 2019; Koçak et al., 2017; Zeanah et al., 2009). Adolescent girls in a collectivistic society are closer to their mothers than boys are to any of the parents (Mastrotheodoros et al., 2019). The absence of a mother figure in institutional care may be a source of frustration and depression in these girls which was reflected in anger in them. Further, as mentioned earlier expression of feelings is more acceptable for girls than boys. This may be another reason for the higher level of anger in girls as compared to boys in the current study.

As not much research is available regarding the relationship of loneliness and gender in institutionalized care in Pakistan, further studies are needed to explore this phenomenon and to understand the reasons for aggression in individuals living in these institutions. What also needs to be understood is the quality of care and guidance provided in these institutes which may be another factor for the relationship of the variables in the study.

Globally, a lot of work has been done to find out the costs and benefits of institutionalized care. Keeping in mind the physical and mental health concerns of children and adolescents residing in there, there are strong recommendations for the deinstitutionalizations and suggestions to promote home-based care for children and adolescents (Goldman et al., 2020). Internationally teams are working to restore the physical and mental health loss of these children through different programs and therapeutic trials. Current research tried to set a background for the upcoming researches and provided evidence of the need for culturally adapted work in Pakistan. This study strongly recommends the development of these types of culturally adapted interventions for the sufferings and psychological distress of these adolescents that remained unattended.

Limitations, Suggestions & Implications

Though this study sets up a background for the upcoming researches, here are some limitations to be addressed. There are some other validated instruments available, measuring multi-dimensions of loneliness instead of uni-dimensional (Sønderby & Wagoner, 2013). The use of a multidimensional tool would have helped to explore different dimensions of loneliness Moreover, longitudinal studies are suggested to assess the causal effect of loneliness on different aspects of aggression. The present study highlights the need for the allocation of psychologists in the institutionalized care centers where children live without their parents. Moreover, this study highlights the area to be work on, for policymakers as well by giving them insight about the issues.

References

Anjum, W., & Batool, I. (2016). Translation and cross language validation of UCLA Loneliness Scale among adults. Science International, 28(4), 517-521. http://www.sci- int.com/pdf/17542882811%20a%20517521%20Wahida%20Anjum %20-2-Physho-- LHR--14-1-17.pdf

Atwine, B., Cantor-Graae, E., & Bajunirwe, F. (2005). Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine, 61(3), 555-564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018

Ayalon, L., & Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2011). The relationship between loneliness and passive death wishes in the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(10), 1677. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001384

Baron, R. A., & Richardson, D. R. (2004). Human aggression. Springer Science & Business Media.

Batool, S. S., & Bond, R. (2015). Mediational role of parenting styles in emotional intelligence of parents and aggression among adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 50(3), 240-244. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12111

Berens, A. E., & Nelson, C. A. (2015). The science of early adversity: Is there a role for large institutions in the care of vulnerable children? The Lancet, 386(9991), 388-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61131-4

Bos, K., Zeanah, C. H., Fox, N. A., Drury, S. S., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nelson, C. A. (2011). Psychiatric outcomes in young children with a history of institutionalization. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 19(1), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229.2011.549773

Buss, A.H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452-459. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452

Carrizales, I. D. (2007). Loneliness, violence, aggression, and suicidality in incarcerated youth. [Unpublished Bachelor Thesis]. St. Edward’s University, Austin.

Chang, E. C., Sanna, L. J., Hirsch, J. K., & Jeglic, E. L. (2010). Loneliness and negative life events as predictors of hopelessness and suicidal behaviors in Hispanics: Evidence for a diathesis stress model. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(12), 1242-1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20721

Chung, J. E., Song, G., Kim, K., Yee, J., Kim, J. H., Lee, K. E., & Gwak, H. S. (2019). Association between anxiety and aggression in adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1479-6

Csáky, C. (2009). Keeping children out of harmful institutions: Why we should be investing in family-based care. Save the Children. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren .net/library/keeping-children-out-harmful-institutions-why-we-should-be-investing- family-based-care